Can the Republic Survive Corrupt Presidents?

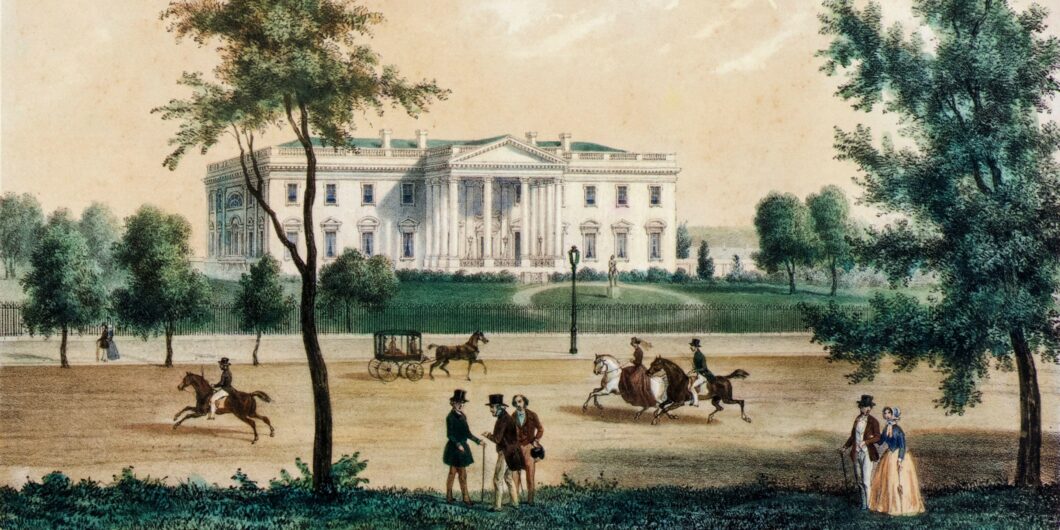

In October 1800, on his first night in the Executive Mansion in Washington, DC, John Adams wrote home to Abigail that he hoped “none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.” That statement now adorns the State Dining Room in the White House.

Adams may be often quoted, but we seldom consider that his hope was not a mere moral exhortation. It was a statement of practical necessity. In the founding era, the question of executive power was a profound—and profoundly difficult—one. Having separated the colonies from Britain, and having embraced republican government, defined as the antithesis of despotic monarchical government, the question of how to reconcile effective executive power with republican government arose. It is the executive power side of Adams’ oft-quoted line that “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Several of the early state constitutions, like the US government under the Articles of Confederation, dealt with the question by establishing weak executives. But in the decades after the Revolution, those constitutions were not working terribly well. The people of Pennsylvania, for example, jettisoned the weak executive outlined in their 1776 Constitution in the early 1790s. They found that it simply was not well-suited to governing.

Others in the founding generation believed that executive power could be reconciled with republican principles as long as the holder practiced virtue, in both senses of the term. Virtue comes from the Latin root vir, or man. Our English word “virtue,” partly means “manliness.” And in that sense, it is bound up with executive power, bold decisive “manly” action. As Adams noted in his influential 1776 pamphlet “Thoughts on Government,” the executive should be a single individual so that he may act with “secrecy and dispatch.”

Yet the Founders’ concept of “virtue” also has a Christian and moral element. In the Massachusetts Constitution, Adams included a clause advocating “a frequent recurrence to the fundamental principles of the constitution, and a constant adherence to those of piety, justice, moderation, temperance, industry, and frugality.” That constitution, not coincidentally, featured a fairly strong executive, elected by the people, and possessed of a qualified veto on legislation. A virtuous executive exercises judgment in approving or vetoing bills, and, when enforcing and defending the laws and the state, conducts bold, decisive legal action for the common good. A good, republican executive ought to possess the virtues Adams outlined in both senses, Latin and Christian.

Insuperable difficulties are posed to the republic when executive power is held by dishonorable men: men who lack virtue. The kind of men who in private life think it unnecessary to pay their bills, plagiarize, cheat at golf or on their wives, or who use the office to help line their own pockets. Above all else, though, an unvirtuous president would not care to make a good-faith effort to distinguish between reasonable and unreasonable uses of executive discretion.

This sort of man sacks the foundation upon which we build a republican executive. The deference which we must give the executive no longer holds, because we cannot assume that he is acting in good faith when he claims to be enforcing the law. But to function properly, the executive needs deference. Men who can act boldly and decisively when lawyers are constantly looking over their shoulders and pointing to hundreds of thousands of pages of legal code which limits their actions are few and far between.

Adams was, in the founding era, Mr. Checks and Balances. He, more than any other single figure, put that concept on our constitutional map. His notion that “power must be opposed to power and interest to interest” is central to his Defence of the Constitutions. By contrast, Madison’s “ambition must be made to counteract ambition” in Federalist #51 is merely an “auxiliary precaution.” Even so, Adams recognized that there are ways in which it is in the nature of executive power to make structural checks rather hard to create. There are, and must be actions that are matters of executive discretion.

Adams was quite aware of that problem. Consider another, less well-known statement by Adams in an 1812 letter to Jefferson. “Good God! Is a President of US to be Subject to a private Action of every Individual? This will Soon introduce the Axiom that a President can do no wrong; or another equally curious that a President can do no right.” An interesting turn of phrase. The old English line was that “the king can do no wrong.” That line was, as Adams knew, a legal principle. There was no redress against the person of the King. He could not be cashiered, even for gross misconduct, short of revolution at least. Hence, as a rule, one who was aggrieved blamed the King’s ministers. In principle, the King was only empowered to act in ways that were legal, in accord with the very law that made him King, but in practice, there was no way actually to gain redress against the person of the king. In principle, the US wanted to be different. In practice, that was difficult.

One cannot allow the president to be above the law.

What prompted Adams’ comment to Jefferson was an 1811 lawsuit by Edward Livingston against Jefferson for acts Jefferson took when he was president. Livingston had been a Congressman in Jefferson’s party and Mayor of New York, but clashed with the President over land claims in the Louisiana territory. President Jefferson confiscated land Livingston claimed as his own, claiming it was federal property. Livingston sued Jefferson personally, and won in Louisiana’s Courts, but in an 1811 case, Chief Justice Marshall ruled against him, focusing on the question of jurisdiction. Marshall was on Circuit in Virginia, not sitting as Chief Justice in Washington, DC. Jefferson’s residence in Virginia did not, he held, make it reasonable to litigate this case in a circuit Court in Virginia. In other words, Marshall found a way to dodge the case. He understood that courts are not designed to deal with cases like this, where the line between legitimate presidential action and corrupt partisan action is almost impossible to decide in any clear way.

That Marshall found a jurisdictional dodge was in a way, an echo of Adams’ point. Marshall thought that Jefferson was extremely misguided politically. He had no personal desire to save Jefferson’s bacon. Yet he also understood executive power, and the difficult problem it presented a government of laws, not of men. That Livingston might sue Jefferson personally was the key issue, one that trumped whatever the narrow issue of the land claims case was. It was a terrible precedent to make any such action litigable in that way.

Marshall understood that there was no limiting principle to lawsuits targeting the chief executive personally. Given how partisan minds work, to allow personal lawsuits against the president, either during or after his term of office, would almost inevitably entail subjecting every president to regular lawsuits not against the US government, but, instead, against each individual who holds the Presidential chair. When Adams raised the possibility of deciding that “the President can do no wrong,” he was suggesting that the abuse of lawsuits might lead, as perverse incentives often do, to a perverse result, a determination that such lawsuits are always out of bounds.

This problem is particularly acute for us today. The more lengthy and complicated our legal code becomes, the more likely it is that there will be a plausible legal claim against any government action, or private action for that matter. Given the expansion of federal power, there are more areas in which the president will have to exercise judgment. And, given the expansion of our legal code, the number of ways it is possible to be on the wrong side of the law in some technical way has grown exponentially. The number of instances in which good lawyers, acting in good faith, disagree about what is and is not legal grows regularly. Hence it grows ever more likely that policy decisions, partisan political decisions, and legal understandings are very difficult to separate. They always were difficult to separate in many ways, but the more government does, the more the problem grows. Hence there are ever more decisions that might, from this perspective, involve the president personally, rather than merely involving the office, as a matter of law. And a president cannot do his job if he is always worried about legal actions. A president must, as Adams said, be able to act with dispatch. As President Grant said, “I am a verb.”

Adams’s wisdom can help us understand the complexity of the problem. There is a danger either way with executive power. It was a bad idea to suggest that the president would never be subject to lawsuits in his personal capacity, and it was a bad idea to subject him to such lawsuits. Both are problematic.

To say that a president should not be subject to any personal lawsuits was to put him above the law. This was anathema to Adams. The president is not an unaccountable king or emperor. Recall that Adams defined a free republic not as a form of government, but rather as “a government of laws, not of men” in his writings from 1775 onward. Chief Justice Marshall used the phrase as part of his justification of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison. The president, empowered by the Constitution, is subject to the Constitution and the laws passed under it. To say that the president generally is not subject to legal liability for his actions is, given human nature, likely to create abuses by the executive.

On the other hand, as a practical matter, making the president subject to private actions was also problematic because it was extremely likely to gum up the works of each and every administration, at least of any administration that had significant partisan opposition. And that would almost inevitably result in bad public policy.

This dilemma demonstrates the true danger of electing bad men to the presidency. One cannot allow the president to be above the law. On the other hand, the practical reality is that having a president who is regularly subject to personal lawsuits for actions that are legally questionable is a very real problem. And once that turn has been made, it would be, Adams knew, all but impossible to undo it, regardless of who was president. Every president will seem corrupt, even if he is, in fact, much better than average.

In his first night at the White House, John Adams was praying that the US would never have to face the enormous practical problem of corruption, in addition to the more obvious moral one. Adams feared that the result of corruption would be a turn toward monarchy. Interestingly, Madison did too. In considering the problem of holding the president personally liable for the use or abuse of his discretion, in other words, we see a return of the problem of the republican executive.