Judgment and Humility, Providence and Free Will

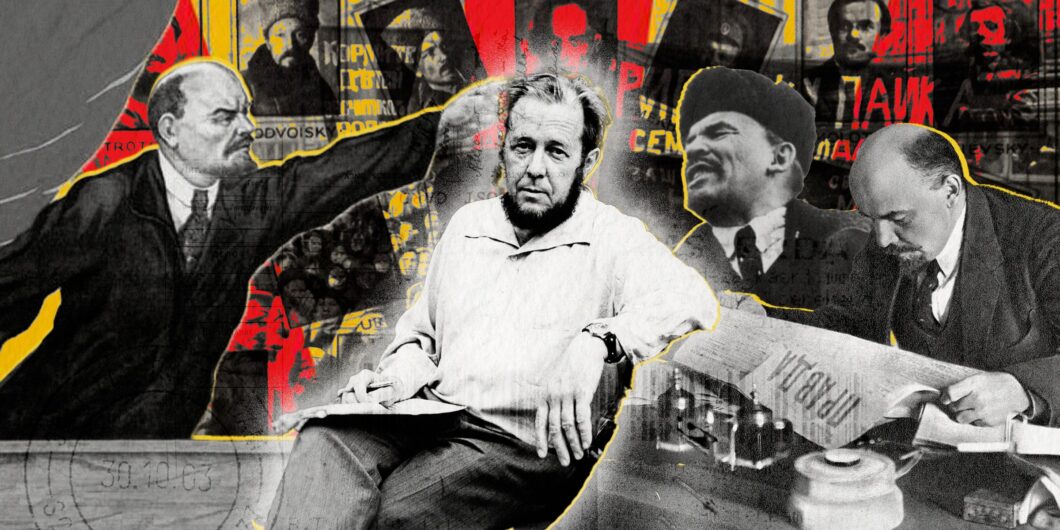

Daniel J. Mahoney’s “Rekindling the Sparks of the Spirit” rightly views Solzhenitsyn’s great work as a tool by which the Western world, all too eager to follow the “road to catastrophe” that led to the gulag archipelago, might relight the fire of “those scruples, those essential elements of our humanity” that will guide us on ways of peace. Those elements of our humanity, he tells us, are “common sense and moral conscience where good and evil first come to sight.” Mahoney identifies the means by which Solzhenitsyn conducts this “experiment in literary investigation” as a combination of history (gained from documents and oral accounts) and memoir. The latter aspect is certainly filled with details, but the details are given for the purpose of “the search for self-knowledge in a manner that he himself calls Socratic.” The self-knowledge he sought is not merely an account of his own soul or experience but of “the truth of the soul and the order of things.”

What accounts for its particular power? One way of saying it might be that in mixing different kinds of writing, objective accounts (such as Soviet laws, regulations, juridical decisions, practices, facts, and figures) together with those deeply personal moments of reflection, the fullness of what it means to be a human being under pressure is given a universal scope. As massive as The Gulag Archipelago is, the longueurs that are encountered in the factual presentations provide the necessary ballast by which this “epic poem,” as Natalia Solzhenitsyn calls it, comprehends not only the scale of Soviet repression but the breadth and depth of the human soul. After all, the soul’s journey involves not only the grand moments of action and passion, violence and suffering, but the unseen and often unconsidered legal and bureaucratic acts that provide a scaffolding for them.

Some might be tempted to say, as Samuel Johnson did of another epic, Paradise Lost, that it “is one of the books which the reader admires and lays down, and forgets to take up again. None ever wished it longer.” I do not think this is quite right for either work. But with regard to The Gulag Archipelago, such a judgment truly does not fit. To fully appreciate the scale of the epic, the vast amount of detail is essential to the overall effect. Even if one does not return to sections on engineering, logging, judicial decisions, or particular camp regulations over and over again, they often present fascinating material in their own right for those who are in these fields. Those bothered by the advancement of the woke agenda in science might very well turn again to the treatments of engineers, chemists, and agronomists outside and inside the gulag.

Even if one has no direct interest in some of the subjects, the facts are presented with Solzhenitsyn’s incredulity and sarcasm as he recounts the insanity of the Ideological Lie as it was told and enacted in countless little lies and absurdities. Instead of the grand figure of Milton’s Satan with titanic gestures, too many of the characters along the way were small and absurd men who said things that resembled those uttered by the boss in a Dilbert cartoon. A perfect example is Solzhenitsyn’s account of one of the first big trials in Soviet history, prosecuting a newspaper that dared to publish an opinion piece with statements about foreign policy contrary to official doctrine. When the elderly editor, P. V. Yegorov, defended himself by saying the article was not slanderous, “Krylenko retorted he would not conduct a prosecution for slander (why not?), and that the newspaper was on trial for attempting to influence people’s minds! (And how could any newspaper dare have such a purpose!?)”

But most who return to this work are returning to that personal voice of Solzhenitsyn, the one that tells us of his own journey not just in and through the gulag system, but into the heart of humanity. And that journey, as the endlessly but never excessively quoted line of his has it, is a journey to a broken land on which one side is good and the other evil. The sarcasm of the narrator of official atrocities or absurdities does not take away from but adds to the vulnerability of the narrator of personal foibles and slow growth of the soul. Judgment of the truth and falsity of systems, actions, and even other souls under and beyond the barbed wire is in no way opposed to the judgment of self that is the province of humility. There is nothing here of Mark Twain’s jibe that “Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits.” If autobiographical works are too often the occasion for the settling of scores, the “I” who is revealed in this work knows he spent many years under the delusion that he knew the score.

Judgment, humility, freedom, free will: these are the flints by which the vivid sparks are lit in this classic whose value is just as great fifty years later.

“Looking back,” Solzhenitsyn writes in the chapter titled “The Ascent” of volume two, “I saw that for my whole conscious life I had not understood either myself or my strivings. What had seemed beneficial now turned out in actuality to be fatal, and I had been striving to go in the opposite direction to that which was truly necessary to me.” This act of turning around—or conversion—seems true because it has been prepared for by 1,200 pages of narrative in which Solzhenitsyn, the former military hero and now ordinary zek, often seemed, as he described many others, “muddled” intellectually and spiritually. There is a fundamental trustworthiness about this narrator whose confessions of ignorance, naivety, pride, and other sins keep popping up whenever he accounts for his own behavior. Like the Roman poet Terence, nothing human is alien to him. Even when he ponders how he did not turn completely to evil, there is nothing of the moral braggart.

The famous lines about good and evil in the human heart are in the chapter about the Bluecaps, those responsible for the hideous interrogation with which one’s experience of the gulag began—and which he had described in horrific detail in the preceding chapter. He describes these men as possessed by those deadly poisons of “greed for power and greed for gain,” observing that “one does not even remember their names, let alone think about them as human beings.” Yet after describing in even more detail their action and manner, Solzhenitsyn stops for a reality check or, better yet, an examination of conscience. “And just so we don’t go around flaunting too proudly the white mantle of the just, let everyone ask himself: ‘If my life had turned out differently, might I myself have not become just such an executioner?’” He answers for himself, “It is a dreadful question if one answers it honestly.”

One might well simply attribute his own destiny to moral luck or a quirk of his constitution. Yet Solzhenitsyn sees something deeper and purposeful in his own life. In the poem “Acathistus,” included in “The Ascent,” which was written “from the pillow of a hospital patient, when the hard-labor camp was still shuddering outside the windows in the wake of a revolt,” Solzhenitsyn described his own understanding of what had kept his will from a definitive turn toward evil. The fifth stanza (in the translation by Ignat Solzhenitsyn) expresses what theologians call divine providence:

Not my reason, nor will, nor desire

Blazed the twists and the turns of its road,

It was purpose-from-High’s steady fire

Not made plain to me till afterward.

There is nothing of the pat answer in this understanding. He ends the chapter with gratitude for his years in prison. “I nourished my soul there, and I say without hesitation: ‘Bless you, prison, for having been in my life!’” Yet a final parenthesis speaks uncomfortably. “(And from beyond the grave come replies: It is very well for you to say that—when you came out of it alive!)”

God’s ways are unfathomable.

And even for those who were returned, the mysteries of providence do not dissipate. Solzhenitsyn’s chapter about release from the gulag in the final volume, “Zeks at Liberty,” provides the uncomfortable realization that the divine will to allow one to die and one to be released does not always seem easy to decipher either. For freedom from the gulag does not equal freedom of the soul. Solzhenitsyn quotes (as he often does) a proverb: “The hard times brace you, and the soft times drive you to drink.” The nourishment of the soul remains a task whether in or out of the prison camp. And “out” may well be more difficult. Better outward circumstances, even more legal and political freedom, are a trial of our free will just as much as bad circumstances. They can complicate that Socratic search for self-knowledge just as much as the gulag’s absurdities do. And the will must be engaged if one is to attain or keep freedom.

Judgment, humility, freedom, free will: these are the flints by which the vivid sparks are lit in this classic whose value is just as great fifty years later.