The Limits of Class Analysis

Professor Bruce Frohnen has written a thoughtful critique of contemporary conservative arguments, noting that conservatives are often too hesitant to directly address questions of class. He is correct that this is a weak point in conservative analyses of modern social ills. This weakness is understandable when one considers the degree to which the mainstream conservative movement has preferred to use individuals as the primary unit of analysis, especially when they lack an alternative that does not seem to set the stage for collectivism.

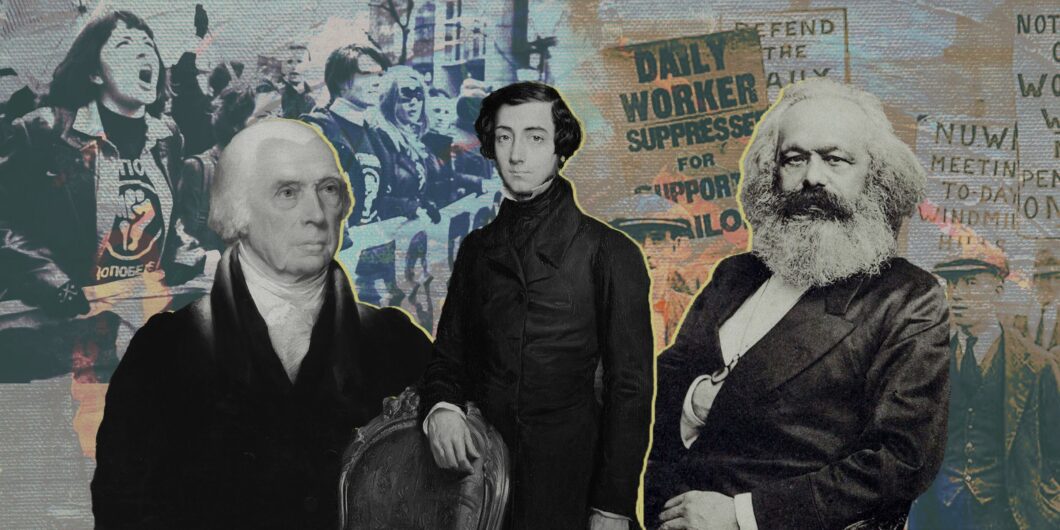

I have made similar critiques of conservatives in my own work. In my last book, I argued that conservatives have given insufficient attention to the role of group identity. When it comes to politics, the groups we identify with are at least as important to us as our specific economic interests. The fact that so many wealthy Americans donate money to the party that ostensibly supports wealth redistribution, and so many poorer people support the party that is committed to giving those same wealthy liberals tax cuts, seems to indicate this. Frohnen argues that we need to expand our understanding of class beyond the Marxist approach, which ties class “completely to the means of production.”

In defense of conservatives, it is probably better that they err on the side of giving class, faction, or identity, too little attention, rather than too much. The case for individualism is strong. Frohnen nonetheless makes many trenchant arguments that all conservatives should consider. Unfortunately, his essay lacked specific, concrete suggestions for what conservatives would do differently if they sought to follow his advice.

Reading Frohnen’s essay, I was reminded of Frank Meyer’s insistence that individualism must be conservatism’s foundational principle: “All value resides in the individual; all social institutions derive their value and, in fact, their very being from individuals and are justified only to the extent that they serve the needs of individuals.” In many respects, Meyer provided a sound approach to politics. Frohnen is nonetheless correct to note that those “associational classes that make up the traditionally rich, overlapping structure of American life” are essential to all of us. We are not mere atomized individuals, seeking to maximize our personal utility. We each have multiple identities and groups that we consider “our people.” These different identities, which are sometimes connected to economic production, but sometimes not, are essential to our understanding of ourselves and our place in society and politics.

Because our various group identities and interests are so essential to us as human beings, Frohnen argues that they must be included in our discussions of policy: “Government, then, properly is a matter of maintaining peace and goodwill among the fundamental groupings that make up any society—from rich traders to mechanics to guilds to lawyers, priests, and the like, thence to families, churches, and other local associations.” This seems like sound advice, but I am not sure what this would entail, especially since some of his examples seem anachronistic. How should the state take “guilds” into consideration? What kind of “local associations” does he have in mind? Robert Nisbet documented the decline of these kinds of organizations seventy years ago, and that trend has only accelerated. Before they can have a seat at the table, they need to exist.

It is a problem that so many intermediary institutions have lost influence and authority as power has accrued to the national government. This process seems so advanced, however, that I am not sure what policy changes could reverse it. Returning more political power to individual states and communities would presumably be a good start, but most conservatives already endorse that policy. I hope that Frohnen will provide further practical solutions as he continues to write about these ideas.

Frohnen brought up religion, noting accurately that religion is an essential element of culture. I am, however, not sure how one incorporates a discussion of religion into a new approach to class. Can we, in the United States, speak of a religious “class”? In other contexts, we could speak of a clerical class that played an important role in government. That has never been the case in this country, where religious diversity has always been the norm.

Frohnen also mentioned Tocqueville in his discussion of religion, but I must point out that Tocqueville argued that religion was so strong and widely embraced in America precisely because church and state occupied separate spheres. As Tocqueville argued, when it becomes just another political faction, attaching itself to a particular political agenda or political party, religion risks alienating large swathes of the population. His argument in Democracy in America remains sound:

If the Americans, who have given up the political world to the attempts of innovators, had not placed religion beyond their reach, where could it take firm hold in the ebb and flow of human opinions? Where would be that respect which belongs to it, amid the struggles of faction? And what would become of its immortality, in the midst of universal decay? The American clergy were the first to perceive this truth and to act in conformity with it. They saw that they must renounce their religious influence if they were to strive for political power, and they chose to give up the support of the state rather than to share its vicissitudes.

This is a very important point. Ideally, religious institutions in the United States should remain at least somewhat aloof from the fluctuations of partisan politics. Unfortunately, we increasingly find that religious identity is linked to partisan identity, with Democrats rejecting conventional religion in the name of party solidarity, and too many Republicans claiming the Christian label as a partisan bumper sticker, rather than out of genuine belief. It is possible that I do not understand how Frohnen wants to incorporate religion into his discussion of class. I encourage him to clarify this.

Frohnen’s argument that conservatives should think about class, as he understands the term, is correct. Doing so would not even be at odds with a commitment to individualism, if we recognize that class in this sense is very important to most individuals.

Frohnen cites Russell Kirk in his essay. My frustration with Frohnen’s argument aligns with my primary complaint about Kirk. Although his work contains much wisdom, Kirk often failed to connect his broad ideas to an obvious policy agenda. In some cases, it was not always obvious what, exactly, Kirk was even talking about. Kirk had a habit of making grand statements about “Permanent Things,” without specifying what those things were or how they were reflected in the concrete reality of our politics. Frohnen’s arguments about class-based analysis seemed to suffer a similar shortcoming.

The essay also provided little analysis of the various classes he wants conservatives to take seriously. This was likely due to space limitations. He did, however, describe “the lawyerly class” and its role in American life. Frohnen, a law professor, takes a dim view of today’s lawyers: “Abandoning their duty to uphold the law of the land, especially as embodied in its written and unwritten constitutions, the class of lawyers increasingly has seen itself as the champion of ‘oppressed’ classes seeking special privileges from the federal government and transformation of America and its people.”

I am not convinced that today’s lawyers are driven by emotions such as the “resentment and envy they feel in themselves.” It seems altogether more likely that most of them are simply working within the existing system in ways that bring themselves maximum advantage. I hope that Frohnen is incorrect about this, as reforming the personal character of lawyers (or any other large group) strikes me as a formidable task. We should hope that change can come from reforming the incentives of our legal system. In either case, I wish Frohnen had given some additional guidance on how we might foster improvement.

I agree with Frohnen’s conclusion that it is “sound political science to note how various government programs are designed and/or used to increase the power and wealth of politicians, lawyers, corporate heads, and ‘public’ unions.” This is a good starting point, but don’t conservatives already do this? Their solutions may be unrealistic or based on incorrect assumptions, but it would be unfair to suggest conservatives have neglected the importance of incentives and institutional design.

Frohnen’s argument that conservatives should think about class, as he understands the term, is correct. Doing so would not even be at odds with a commitment to individualism, if we recognize that class in this sense is very important to most individuals. Such an approach could help reorient conservative thinking, giving it a role in reviving the associational life that was once a hallmark of this country.

Some trends may be outside of government control, however. Is the “geographical isolation and intermarriage of the well-connected, credentialed, and wealthy in the United States” the result of deliberate policy? That is possible, but technological changes and greater geographic mobility strike me as equally plausible explanations. If that is the case, reversing the trend is much more difficult. I look forward to learning more of Frohnen’s thoughts on this.

I again concede that I may have misunderstood key elements of Frohnen’s argument. I agree with many of the sentiments he expressed in his essay. However, without more specifics about what conservatives should be doing differently, it is hard to embrace or denounce what he is saying. I say this in the spirit of friendly critique: I hope he will elaborate further in the near future.