Our Corporate Oligarchy

During a remote video conference meeting with several coworkers in the spring of 2020, the topic of lockdown orders came up. While most eagerly favored the measures, I asked, “What about small businesses forced to close? People stood to lose their livelihoods, most of whom had spent much of their lives building, without recompense.” One highly educated and well-compensated colleague derisively replied, “It is for the greater good.” The contempt in her voice was apparent. At this moment, I realized the veil of feigning compassion for working-class and small-town Americans was over. The pandemic and government-ordered lockdowns exacerbated and laid bare, decades in the making, the chasm between the elites, their constituents, and the common man and woman.

Before the conflagration of the Floyd riots spread across the country, there was a spate of protests by aggrieved craftsmen and women who were denied the opportunity to earn a living by lockdown measures. Media personalities and politicians quickly turned on these dissenting voices, especially those unable to work remotely. Of course, this attitude is not new. Class division has always been present throughout American history and, until the 1980s, had been a significant concern of conservative philosophers.

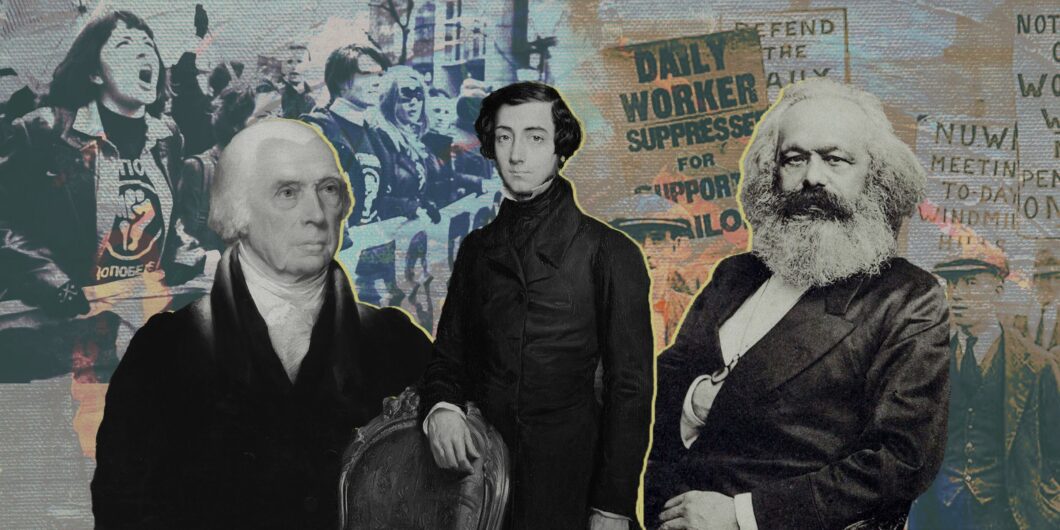

American conservatism, arguably rooted in the federal tradition enshrined in the Constitution, continuously accounted for hierarchy and the division of social and economic class distinction. As discussed by Bruce Frohnen’s lead forum essay, a discussion of class difference and its role within American society is most certainly warranted. Yet, conservatives often overlook the role of capitalism, specifically corporate capitalism, in fomenting upheaval and furthering class division in American society. While free markets and private property rights are paramount to all American conservatives, corporate capitalism has wrought chaos throughout the class strata that has been a permanent feature in American society.

The rise of corporate capitalism in the nineteenth century disincentivized the wealthy ruling class from its paternalistic obligations to those in the middling and lower classes. These obligations were built upon generations of experience and were intended to minimize social discord and upheaval. While these lessons should have been reinforced by the revolutions of 1848 in Western Europe, they were largely ignored in the name of progress and modernization throughout the Western world. Capitalist elites and progressive governing institutions dismissed the value of communal relationships, tradition, and cultural practices as unquantifiable and did not serve the needs of a nascent industrializing economy. Although modern conservatives may view such criticism of corporate capitalism as Marxist, it is, in fact, deeply rooted in the conservative tradition.

Of course, we do not live in nineteenth-century America. However, critiques of capitalism and class division are more necessary now than in the past. Even as Thomas Jefferson famously acknowledged the existence of a natural aristocracy based on talent and merit, his contemporaries did not dismiss out of hand the necessary role that those on the lower strata of society perform. Likewise, many who had attained positions within our informal aristocracy abided by the concept of noblesse oblige, which recognized that an ordered society in part depends on the obligation elites owed to those who labored in the middling and lower strata of society to whom the elites owed their position. While the concept was draped in virtue, it also had a practical application to preserve social tranquility and avoid turmoil.

The ascendency of industrial capitalism challenged the old order and injected turmoil into the daily lives of people across the socioeconomic strata of society. As Frohnen points out, “associational life” has been under constant threat, particularly in the twentieth century. Markets for goods and services expanded far beyond the local or regional, and to keep pace, many found that they had to borrow money from local banks who, in turn, held obligations to larger remote institutions. As a result, the relationship between borrower and creditor was depersonalized. Borrowing became necessary for farmers to keep abreast of efficiencies demanded by market prices. The change, in turn, placed considerable financial pressure on families who were forced to relocate to towns and cities to work in factories and mills. This new arrangement was complicated for many families who had previously lived an agrarian lifestyle. John Crowe Ransom described this new arrangement in the Southern agrarian critique of industrial capitalism I’ll Take My Stand as hard, fierce, and insecure. Separated from their folkways, extended families, communities, and centers of religious and civic life, many ordinary Americans struggled to make sense of their changing world.

By the mid-twentieth century, some semblance of order had returned. American servicemen and their families who had suffered through the Great Depression and separation during World War II were eager for remuneration for their sufferings. They found a reprieve in the post-war economic prosperity that resulted in the construction of new, clean, suburban communities and access to inexpensive material goods. Despite this, the corporate capitalists, and by extension, the state, were unsatisfied and attempted to homogenize the cultural landscape and centralize power to create an American-led global corporate regime. The poor and working classes soon discovered that the revolutionary project of global corporate capitalism would inject further turmoil into their lives.

In the decades that followed, and through the opening of other markets worldwide, the secure position that American labor once held began to slip away. Technology and efficiency flattened society and culture. Respect for the land where families had lived for generations, as well as churches, graveyards, and other places once deemed sacred, were dismissed as insignificant by both government and capital alike. Everything had a price, and everything was for sale.

This destructive tendency inherent within industrial capitalism was, for a period, embraced by many who had experienced the untold hardship and poverty of earlier decades both in America and abroad. Government and capital grew ever more intertwined, and Americans, particularly those in the lower classes, would suffer as a result. Moreover, Americans became increasingly enamored with prestige, status, and materialism. For those who could not achieve these ends, many turned to forms of self-abuse, such as alcoholism, drugs, or intense social isolation. Society turned inward on itself, even as markets for goods and information exploded globally. As Peter Kolozi eloquently stated in Conservatives Against Capitalism, “As economic thinking became dominant, civilization’s focus turned to the pursuit of self-interest, profit, and material consumption of luxury, which led to decadence.” Self-interest and aggrandizement allowed so-called conservatives to blame those in the lower strata of socioeconomic life for their failings. After all, so-called conservatives famously paraded about the mantra that anyone could succeed in America if they worked hard enough.

Instead of seeking to sustain the unsustainable fantasy of economic growth at all costs, American conservatives should dismantle nearly every unconstitutional apparatus of the central government and transfer that authority back to the states and, by implication, the people.

It was never that simple. Frohnen asserts that the displacement of “families, states and local civil and religious associations” was partly a result of the dispensation made by the central government. This was exacerbated by a corporate oligarchy that utilized the government to create a regulatory apparatus designed to further its authority, often to the detriment of small business owners, independent tradesmen, women, and the many blue-collar workers who toiled in American manufacturing. Any person or organization that questioned or objected to corporate power was often scorned as liberals or socialists by prevailing voices in the Republican Party.

Corporate capitalism found a willing friend in the Republican Party. They upheld economic interests to the detriment of societal stability, dismissed class division, and quickly attempted to dismantle the welfare state whilst doing almost nothing to buoy the fortunes of the family and civil society on which many who survived on the periphery of material wealth had depended for generations. The virtues of restraint, participation in civic life, and honesty eroded in the face of capitalist virtues such as profit-seeking and instant gratification. Noblesse oblige made way for sneering comments such as, “Learn to code.”

In the face of intense competition for educational, career, and materialistic achievement, identity shifted from place, tradition, and family to race, sex, sexual, and gender orientation. The younger generation, particularly those who had grown up in economically prosperous circumstances, scorned class differences and found purpose in upholding radical notions of privilege and new associations divorced from traditional virtues and institutions. Capitalists and the government were quick to foster and nurture these social cleavages.

Cultural disruption and the “new morality” embraced by corporate capitalists have done everything in their power over the last decade to undermine further remnants of civic and religious associations, traditions, and folk cultures of nearly every long-standing ethnic group in the country. For the insulated elite classes, this created little disturbance; however, for the geographically disparate and ethnically diverse lower strata of American society, the results were profound. Separated from their history and traditions, corporate capitalists, along with many in the Republican Party, encourage these “great unwashed” to relocate for economic opportunity, often into cosmopolitan enclaves. As GDP increased, alienation, isolation, and depression followed.

While there may be little that the central government can do to reverse course and maintain its hold on the lives of Americans, there is a role for conservatives and conservatism to remedy the deleterious state of our society. Instead of leaning into a particular brand of libertarianism that would facilitate capitalist influence and authority over government and society, conservatives should restrain the privileges given to today’s oligarchs. Conservatives would do well to remind themselves of the duty of inheritance; we have inherited traditions and values from those who came before, and as stewards, we have an obligation to preserve those for future generations.

We are amidst a continuous revolution sought by corporate capitalists. Instead of seeking to sustain the unsustainable fantasy of economic growth at all costs, American conservatives should dismantle nearly every unconstitutional apparatus of the central government and transfer that authority back to the states and, by implication, the people. Moreover, conservatives should energetically advocate for constitutional federalism and support local governance, civic participation, and limits on interference from outside corporate and financial institutions. Citizens should sense that they have agency over their own lives, and within that will come, with the solid encouragement of state and local officials, organic growth in the associations and cultural traditions will once again assert themselves across every strata of ethnic, religious, and communal life.