It is magical thinking to believe that the United States can run large deficits indefinitely.

Conservatism and Class

For too long, too many on the American right (broadly construed) have insisted that ours is by nature a classless society. Despite evidence to the contrary, it remains almost obligatory to claim that, in our country, wealth and status may affect individual lives but do not forge abiding, self-conscious “class” groups that shape members’ characters, let alone our overall political structures. One critic recently termed paleoconservatives (those who focus on the role of changing social structures in undermining American localism) “right-wing Marxists” for their overt, though far from total, reliance on class analysis. Others on the right, from libertarians to various critics of Donald Trump, emphasize the dangers of a populism rooted in class consciousness; such a movement, they believe, inevitably spurs resentment and demands for political action inimical to free markets, limited government, and (real or imagined) American traditions of political civility. But one need not be a “paleo” conservative or a populist to recognize the abiding role of class, properly understood, in shaping the American political order.

Associational Life

The tendency to reject class analysis out of hand is essentially leftover from the post-World War II “consensus” in which the Republican Party accepted the essential elements of the New Deal in an atmosphere of American economic, political, and military dominance. Confident America could afford a growing administrative and welfare state and afraid to risk dissension during a Cold War, too many conservatives went along with the establishment of a new (anti)constitutional dispensation. This dispensation established congressional authority to regulate the bulk of economic life and implement large-scale social programs that crowded out and even legally displaced families, states, and local civil and religious associations that traditionally tended to the needs of their members. This new dispensation eliminated much of the reason for “lesser” associations to exist; by accepting it, the vast mainstream of political leadership adopted an essentially Progressive understanding of our society. In this view, individuals are better off without that variety of local associations (and the restrictions they placed on individual action) that once ordered our common life. Markets and the safety nets of the central government on this view would protect individuals even as they coordinated our efforts in global political, economic, and military conflicts.

This anti-associational prejudice was energized by the struggle against Jim Crow laws and the “war” against poverty, both of which were painted and waged in increasingly anti-localist terms. It devalued the diversity of (inevitably imperfect) American communities that upheld our constitutional republic. It also left the field of cultural formation open to radicalized educators and government functionaries who worked to replace families, churches, and local associations with directives from administrators within a centralized national state as the shapers of Americans’ characters.

Recent events have made clear the long-term result of this essentially unresisted onslaught of Progressive individualism: the rise of a new, corrupt ruling class. “Emergency” powers from lockdowns to secret censorship and mass surveillance have become common tools of our rulers. A new class of apparatchiks hopping from corporate C-suites to the heights of the bureaucracy, along with their overlords at the highest levels of government-supported corporate life, has become powerful, insular, and hostile to American traditions of self-rule, ordered liberty, and the rule of law.

Charles Murray has shown the increased concentration of wealth and power exacerbated by geographical isolation and intermarriage of the well-connected, credentialed, and wealthy in the United States. And a two-tiered structure of power and privilege has been made manifest in the adversarial relationship between a small class of rich and powerful globalists seeking our society’s fundamental transformation and working Americans who want to be left alone to pursue a life of dignified work and self-government. When one adds to this the successful push to outsource jobs and open our borders in the interests of lowered labor costs and dilution of local culture, it is little wonder that workers and increasingly embattled local elites in our smaller cities and towns have been developing an increasingly common identity and negative view of their status in contemporary America.

Town leaders, local merchants and manufacturers resisting globalist integration, and local workers are decreasingly defined by their differences in wealth and education—let alone their relation to the means of production. Increasingly important is their common interest in salvaging their way of life. The result is not a new class in the Marxist sense, but a new layer of cooperation, a tentative renewal of the much-derided but foundational “boosterism” that characterized settler communities which forged tight internal ties in the competition for recognition and economic success in the old West. Locality has not replaced but rather encompassed and incorporated economics and so strengthened a network of connections and tensions of varying political salience in response to current circumstances. Economic class is, then, one important element in understanding the broader, associational classes that make up the traditionally rich, overlapping structure of American life that is being destroyed by new, powerful factions. The more globalist progressivism succeeds in grinding down this set of connections, the more like simple creatures of economic class—objects of control by forces beyond our control—we all become.

Class in America

Still, those of us styled “traditional” or “cultural” conservatives, often find ourselves criticized for embracing the reality of various class distinctions active from the very beginnings of our republic. But traditionalists like Russell Kirk were not the first observers of a healthy set of broadly defined classes in the United States. There was, for example, James Bryce, the turn-of-the-twentieth-century English liberal and author of The American Commonwealth. He noted that class was important to American political society, though not crucial to our politics in the way it was in Europe because rich and poor were not locked in a binary struggle over power. Rather, rich and poor existed in both major political parties. Class was salient in the United States in a different form, determined largely according to profession.

Bryce outlined the habits and opinions of farmers (and their “hired men”), shopkeepers, working men, the degraded urban poor who were little more than tools of parties within their cities, railroad magnates and other business owners, and professionals, including most prominently lawyers and professors. Also important were the various religious and ethnic associations that formed common minds among Americans, much to the distress of various Marxists. For many years, then, America was a healthy society because it had many classes with differing goals and traditions which sought to compete with and even displace one another, but which were held together by a broader tradition of cooperation fostered by constitutional structures, social norms, and administrative decentralization.

The post-war refusal to recognize class as one element in the organization and the potential undermining of our civil social order has put that order in jeopardy. In particular, the assumption that self-interested individuals will choose actions and policies that uphold our way of life has caused too many on the right to abandon the so-called “culture wars.” Bryce’s lawyers and professors, now corrupted by pride and the will to power, have been left free to train and empower ideologues who seek to destroy our way of life. They have used laws and “diversity” programs to seize control over organizations from schools to government agencies and human resource departments. The result is an increasingly intrusive, pervasive, and high-handed set of class-based structures working to control all aspects of Americans’ lives.

We must address the increasingly destructive tendency to delegitimize all associations that stand in the way of national “progressive” uniformity on all issues.

Social and cultural institutions outside the state can survive only in a society that recognizes people’s natural propensity to form many classes which in turn shape their characters. We must understand what classes are, which ones are active and powerful, and how they interact. Only then can we see the relative promise and danger of various classes, allowing us to foster, oppose, and/or balance them against one another. This was, after all, the logic of our own Constitution. As Madison pointed out in his dour way in Federalist #10, the sheer variety of associations in our far-flung republic allowed for a balancing of classes and interests that would prevent any faction or coalition of factions (classes hostile to our common good) from gaining control of the federal government. Differing functions, rights, powers, and modes of election would prevent the various mechanisms and branches in the federal government from becoming the tool of any of them.

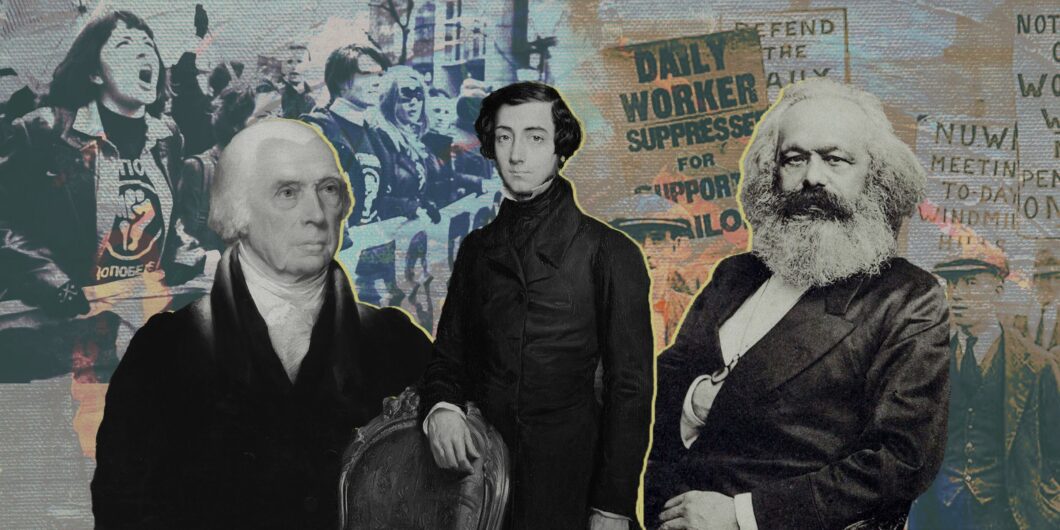

Why, then, are so many American conservatives resistant to even rudimentary forms of class analysis? Why reject a tool of political understanding with a history dating at least from Aristotle, through the English constitutional tradition, Burke, our own founders, Alexis de Tocqueville, and to the present day? A key answer, in a word, is Marx.

Marx’s grand contribution to class analysis was a grand error. He tied class, and with it every class member’s self-understanding, completely to the means of production. Both groups and individuals were, for Marx, shaped in their very being by their place in the great chain of economic production. Workers vs. bourgeoisie is an oversimplification of the Marxian dynamic. There were also the lumpenproletariat, intellectuals, and various other groups as Marx’s followers added one epicycle after another to explain away the failure of reality to catch up with their model of a world moving inevitably toward class revolution ushering in a workers’ paradise. Still, the engine of history and of human nature itself, for Marx, remained economic production.

Unfortunately, this Marxian logic infected American political science, especially through the notion of “interest groups.” On this view, American politics is dominated by conflict between the public interest, which is intrinsically Progressive, and various interest groups, which seek their own economic benefit at the expense of the common good. This is, in essence, a bowdlerization of the understanding of factions laid out most prominently in Federalist #10. Madison recognized that differences in occupation and economic interest forge both commonalities and conflict. He further recognized that these differences sometimes produce motivations, policies, and even conspiracies opposed to the common good. But Madison noted that such conflicts may be tamed through proper constitutional architecture and, at least as important, that they are natural—part of human nature that can be stamped out only through oppression. He also recognized that these factions can be limited and even neutralized by other entirely natural connections rooted in local life. Meanwhile, the Progressive spin on class paints all opposition to an increasingly dominant, intrusive national state as selfish, materialistic, and illegitimate.

Conservatives can and should ignore the Marxian aberration. But we must go further. We must address the increasingly destructive tendency to delegitimize all associations that stand in the way of national “progressive” uniformity on all issues, from identification of economic interests to identification of one’s own sex. And to do so we must reintegrate social and economic analysis by recognizing the “class-ness” of a multitude of associations. Whether rooted in religion, locality, or economic interest, the ties that bind us make up something that can best be understood as “class” because they shape our common interests and even personalities in ways that influence public and political life and that are influenced by economic reality. People will sacrifice much for their faith or love of their ancestral homeland, for example. But very few will accept their own economic destruction, especially if it means most of their fellows must leave in order to survive.

Traditional conservatives especially emphasize how culture shapes human conduct. And culture, as traditionalists often point out, comes from the cult. Man is a religious animal. His religious institutions, beliefs, and practices do more to shape his personality and social reality—including his economic activity—than any other force. Moreover, traditional conservatives recognize that every one of us, and human society as well, has a purpose. We are meant by our very nature for something more than getting and spending, or even building. That something is, of course, spiritual. Those, including some paleoconservatives, who use Marxian terms like “class consciousness” seek a tough-minded “realist” analytic vocabulary that eschews the supposed vagaries of moral discourse. But history provides better models that capture what is right (and generally borrowed) from Marx while eschewing his determinism and simplistic materialism.

The most telling development in Marxian analysis was put forward by Milovan Djilas in The New Class. Here Djilas detailed the emergence of an insulated nomenklatura as a self-conscious, self-perpetuating privileged group within socialist countries. And, one might add, this “new,” bureaucratic class seems equally real and self-interested within the mixed economies of Western countries that have developed their own self-regarding administrative states. Djilas’ understanding of class consciousness as a combination of logical motivations, personal aspirations, and common interests growing out of social cues and changes in cultural structures captures the workings of our social nature within the complex structures we build over time better than any abstraction like “the means of production.”

Class is not the narrow, monolithic reification of Marx’s imagination. Class begins as the mere sharing of an important characteristic by any group. In politics, it means a group of people sharing some politically relevant and important characteristic or characteristics. Class, then, becomes a proper subject of political analysis when shared characteristics combine to make a group politically relevant, which generally involves a capacity for self-perpetuation, influence over important aspects of public life, and effectiveness in pursuing a common goal or goals that shape the social order. A class, then, is much like any other group or community whose members share experiences, histories, and goals—be they economic, religious, ethnic, or geographical—except that it is especially active and relevant in public life.

As in so much, the true “science” of class politics begins with Aristotle. Readers may recall Aristotle’s taxonomy of regimes, with three good and three corrupt versions of constitution, each based on rule by the one, the few, or the many. The best achievable regime form, according to Aristotle, was a mixed constitution. Why? Because the self-interest and self-understanding of each of these classes set them against one another and the common good, necessitating a balancing of each against the other through political and social structures.

Russell Kirk noted that order, the foundation of all we can hope for from political life, “is the harmonious arrangement of classes and functions which guards justice and obtains willing consent to law and ensures that we shall be safe together.” Government, then, properly is a matter of maintaining peace and goodwill among the fundamental groupings that make up any society—from rich traders to mechanics to guilds to lawyers, priests, and the like, thence to families, churches, and other local associations. All of these may form into politically relevant “classes,” depending on how much political power and common identity they secure; as classes, they may serve or endanger the common good. It is only natural that members of various groups should tend to see the common good through a lens focused on the good of their own most salient relationships, companions, and interests. And more selfish, base motives are never absent, especially when there is a public purse to be raided and public power to be used against one’s enemies.

Lacking entrenched, regulated structures of privilege, America’s natural aristocracy was part of a decentralized order that afforded ample opportunities for talent to find success and for regular folk to toss out abusive elites.

Class became increasingly salient and pressing during the early modern era, when monarchs sought to exert their “sovereignty” to the exclusion of other classes. The monarchical party won most of the ensuing, bloody wars. But in Britain, the various non-monarchical classes gained power over time. The balanced constitution flourished, thanks in part to men like Edmund Burke, who fought corruption and royal influence in defense of the old order of balanced, responsible classes, including a public-minded aristocracy and those he termed “new men,” meaning those whose ability and dedication to the public good earned them public respect.

The stage was set, then, for a fundamental break in the Western tradition, between conservators of a social order rooted in a multiplicity of authorities and those seeking to erase class distinctions in the name of equality under centralized power. The French Revolution brought calls for liberty, equality, and fraternity, along with mass murder of the rich, nobles, clerics, and anyone who sought to defend their accustomed way of life. This kind of revolution was averted in the Anglosphere, most importantly in America, where an older kind of revolution, seeking a return to traditional liberties, brought forth a new republic with a Constitution focused on separating government functions, taking account of class, and keeping the central power within bounds by rooting it in the states’ ceding of only limited, enumerated powers.

There were no full-on Marxian classes in the United States because there was no system of privileges. But there were obvious inequalities of wealth, status, prestige, and political influence. Key to the distribution of each in America was the natural aristocracy. Most associated with Thomas Jefferson, the natural aristocracy has much deeper and broader roots. Burke, for example, argued in his Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs that “a true natural aristocracy is not a separate interest in the state, or separable from it. It is an essential integrant part of any large body rightly constituted.” According to Burke, natural aristocrats are those whose conduct and experience-based character earn them general respect and deference; their social position “is formed out of a class of legitimate presumptions, which, taken as generalities, must be admitted for actual truths.”

Lacking entrenched, regulated structures of privilege, America’s natural aristocracy was part of a decentralized order that afforded ample opportunities for talent to find success and for regular folk to toss out abusive elites or leave them behind in a vast open country. Burke emphasized the experiences of people in various honorable callings. His point was simply that our activities and relationships shape who we are. Class forges a kind of common character and consciousness because it is the product of similar circumstances and connections.

Class has always been real in America. But, with the notable exception of slavery and the abiding conflict regarding differences between men and women, there has been a permeability and even overlapping character to class in the United States. Combined with a refusal to accord classes specific political power and privilege and a decentralized administration, this permeability kept elites in check through their constituents’ ability to exit or fight back at the ballot box or in court.

The Lawyerly Class

Near the apex of America’s natural aristocracy was the class of lawyers. Lawyers acted outside any strict line of rich vs. poor. They were, for Bryce, mechanics of order, for Burke authors of rights seen as tools of liberty, and for Tocqueville guardians of precedent and, through it, public peace.

Burke emphasized lawyers’ intrinsic concern for individual rights, which shaped Americans into an unruly people, on the lookout for tyranny. In Democracy in America, Tocqueville emphasized the conservative power of precedent and American lawyers’ insistence upon it: “Their aristocratic inclinations are secretly opposed to the instincts of democracy, their superstitious respect for all that is old to its love of novelty, their narrow views to its grandiose designs, their taste for formalities to its scorn of regulations, and their habit of advancing slowly to its impetuosity.”

The class of lawyers shaped American institutions and characters as it was shaped by active participation in the common law system. Unfortunately, as the unifying forces of American public life (including religion, a functioning multiplicity of authorities, and a generalized respect for tradition) weakened, lawyers were among the first classes to turn on our tradition, in the process becoming both corrupt and corrupting. Abandoning their duty to uphold the law of the land, especially as embodied in its written and unwritten constitutions, the class of lawyers increasingly has seen itself as the champion of “oppressed” classes seeking special privileges from the federal government and transformation of America and its people. Mistaking government policies for legal rights, its members have turned the court system into a locus of political argument more appropriate to systems rooted in French revolutionary ideology than American precedent and common sense. They have all but eliminated constraints on federal power and worked to coopt or destroy the variety of classes and authorities that once kept it in check.

This is both a political disaster and a restructuring of society along new class lines. Despite their pretensions, lawyers are not at the top of the new order. That place belongs to the titans of information technology able to manipulate perceptions and, with them, markets and policies. The second rank belongs to the uber bureaucrats who maneuver between corporate C-suites and agency leadership, reformulating the byzantine rules that prevent the people from understanding, let alone participating in, constitutional self-government. As a class, lawyers are mere tools or unpleasant but useful servants—like professors, public school teachers, and lesser functionaries—of a small group of elites with little connection to any one country or profession. Constantly seeking and being denied the status they crave, lawyers and the rest have become increasingly invested in fostering in others the resentment and envy they feel in themselves.

It is almost as if the current ruling class has sought to make Marx’s predictions come true, except that they have no intention of ceding power to any proletariat. Rather, the goal is to reduce all classes except their own and its servants to the status of Bryce’s desiccated urbanites or peasants. The people are to be made so dependent on government largesse that they will accept their new position, with its utter lack of political agency, in exchange for the current form of bread and circuses—government handouts, semi-legalized narcotics, and an internet drenched in pornography and other mindless addictions like TikTok.

Toward a Balanced Constitution

All this highlights the importance of Aristotle’s central constitutional lesson: stable constitutional government requires a healthy, active middle class, broadly conceived. Only those accustomed to ruling and being ruled in turn can be trusted with political power. America once was a healthy republic, not because it lacked classes, but because it had many classes and was at the same time dominated by a heterogeneous middle class. This nesting of classes—the common occurrence of one class including within itself members of various other classes—should make sense to a people raised within a federal system. Unfortunately, as with so much else, our understandings have been narrowed and simplified by the ideological categories of Marxism and its American offshoot, Progressivism. Moreover, it is easy for those who have profited from the concentration of power and wealth into ever fewer institutions to look down upon the farmers, skilled tradesmen, and other blue-collar Americans whose high school educations now make them officially “uneducated.” But these same people, as classes and as individuals, were an essential part of America’s ruling middle-class coalition and its constitutional republic.

As Bertrand de Jouvenel predicted, overreliance on law and administration has reduced the people to ciphers in a constant fight among elites over who shall control the levers of centralized power. A free people does not compete among itself to control the machinery of government. A free people acts through the various classes to which every person belongs, seeking compromise among themselves while guarding against an overweening central state and keeping in mind that a harmonious ordering of classes and functions is necessary for any political good to exist.

Renewal of this understanding requires, first and foremost, that we understand the makeup of our current, illegitimate ruling class. It is a faction, hostile to our traditions and way of life, that has built machinery it controls through the cooperation of lesser classes, most of which are dependent on its largesse. And it is not conspiracy theory but rather sound political science to note how various government programs are designed and/or used to increase the power and wealth of politicians, lawyers, corporate heads, and “public” unions.

Likewise, an adequate understanding of politics requires that we pay attention to the manner in which bureaucratic authorities use law, lawyers, and the educational system to help the powerful, coopt those who lack strong class identification, and undermine both the middle class and the fundamental social associations in which they and their children maintain the character essential to self-government. Such analysis should not be dismissed as paranoid or un-American. Western civilization has developed it across more than two millennia, honing it in the United States as Americans pursued a fuller understanding of political dynamics. This is the path toward ordered liberty in large, complex societies.