One of the most successful parody accounts on Twitter, Andrew Doyle’s invention offers a picture of intersectional activism’s most deranged impulses.

Lost Horizon

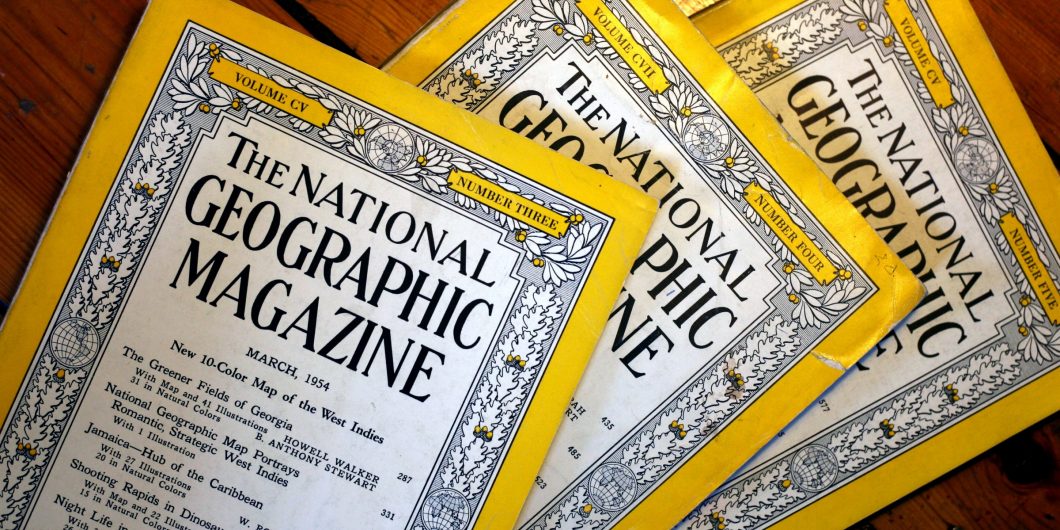

On a cold winter night in 1986, I met my father and the writer C.D.B Bryan at the Irish Connection, a bar in the basement of a building on DeSales Street in Washington, D.C. I was a student at Catholic University who had just published his first article as a professional, a piece on preventing animal cruelty for The Progressive. My father was the Senior Associate Editor of National Geographic magazine. C.D.B. Bryan was the popular author of Friendly Fire, a book about Vietnam. He had been hired by National Geographic to write the book National Geographic: 100 Years of Adventure and Discovery, which would be published in 1987.

My father had invited me to meet Bryan because he knew I had developed a fascination with Vietnam during a high school history class. He also knew that as a young journalist I would be enthralled to meet such an accomplished writer as Bryan who had written for the New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire, Rolling Stone, and the New York Times Book Review. Over pints of Guinness, we three talked about various things—music, literature, sports, what it was like to write a massive history of National Geographic. Bryan expressed delight that I had just professionally published my first article, but added a quip: “The Progressive is a great place to start. I don’t know if you’d want your daughter dating a writer from there, but still.”

We discussed Friendly Fire, Bryan’s book that told the tragic story of Michael Mullen, an American soldier who had been killed by friendly fire in Vietnam. Friendly Fire revealed the lies the government had told about the nature of Mullen’s death. It explored in moving detail how Mullen’s parents, especially his mother Peg, went from staunch patriots to anti-war activists. “He was very proud of the fact that he exposed the friendly fire issue, and the fact that the government was lying to people who were as very patriotic as the Mullens were,” Mairi Bryan, C.D.B.’s wife, said after his death in 2009. “Of all of his works, Friendly Fire was the one of which he was most proud.”

It’s been more than thirty-five years since the night I had Guinness with my father and Bryan. Today, National Geographic reflects an obsession with race, gender, and “equity,” dedicating covers to slavery, feminism, transgender ideology, and Black Lives Matter. In 2017, the magazine ran a special issue on “The Gender Revolution,” parroting the catechism of the transgender faith, with all the logical inconsistencies that go along with it. It’s no surprise that the Western world has gone native into wokeism. Yet because it’s so personal, National Geographic‘s surrender is particularly painful.

The sloppiness of the logic of the new National Geographic, the focus on the latest academic fads, not to mention the poor quality of many of its covers, would have shocked my father’s generation of talent. My father worked with men like Wilbur Garrett, the editor of National Geographic. Garrett was a tough, mercurial, and brilliant man who had grown up poor in Missouri during the Depression. He and my father wanted National Geographic to reflect the real world while also keeping to its tradition of great photography and uplifting travelogues to exotic places. (NatGeo president Gilbert Grosvenor fought Garrett’s idea on an entire issue dedicated to the two-hundredth anniversary of France, an issue that ended up winning the 1989 National Magazine Award.)

Then there was Howard LaFay, a large, hilarious man with wavy back hair cut short who wrote articles for the magazine about Leningrad, Trinidad, and Easter Island. LaFay also wrote about Sir Winston Churchill’s funeral, and a book about the Vikings. An amateur biblical scholar, LaFay covered finds at the ancient Syrian city of Ebla. In World War II, he served for three years with the Marine Corps in the Pacific and was wounded on Okinawa, receiving the Purple Heart Medal. After studying for two years at the Sorbonne in Paris, LaFay was recalled to active duty and served as a captain during the Korean conflict.

Another face I would sometimes see at our dinner table in Maryland was Thomas Abercrombie. In 1957, Abercrombie was the first civilian correspondent to reach the South Pole. In 1965, he discovered the 6,000-pound Wabar meteorite in the Arabian Desert. A few years earlier, in Cambodia, he outwitted an angry mob, eager to tear any American limb from limb, by convincing them that he was French. In the 1991 National Geographic article “Ibn Battuta: Prince of Travelers,” he wrote about the year he spent traveling through 35 countries—from Morocco to China—in the footsteps of the 14th-century Arab explorer. Mr. Abercrombie visited all seven continents, and he seemed to have seen nearly everything on them, around them, and between them. When Abercrombie died in 2006, the New York Times described him this way:

He traveled by airplane (he was sometimes the pilot), sailboat (ditto), canoe, Land Rover, sled, horse, mule, camel, yak and, when all else failed, foot. He sailed the St. Lawrence River, led a train of 400 camels through the Sahara and swam with Jacques Cousteau. He was famous for wrecking cars and went through many. He once put a very small plane on his expense account. He met soldiers and diamond miners, farmers and fortunetellers, wandering nomads and Stone Age tribesmen, emirs and sheiks and kings. For emergencies, he carried wafers of Swiss gold in his pack, and, for bigger emergencies, AK-47’s.

The obit concluded, “With his full beard, compact build and thirst for adventure, Mr. Abercrombie was often likened to Ernest Hemingway. But from the mid-1950s to the early 1990s, his exploits in any given week made Hemingway’s look like child’s play.”

My favorite of all was probably Luis Marden, the real-life most interesting man in the world. Marden was a gentleman, a polymath, and an adventurer—and he knew his French wines. The son of an insurance broker and a teacher, he grew up in Quincy, Massachusetts, got interested in photography, and was hired by National Geographic at age 21 never having gone to college. A pioneer of underwater photography, Marden spoke five languages. His house, on the banks of the Potomac River in Virginia, was custom built for him by Frank Lloyd Wright. Marden found the wreck of HMS Bounty and dove with Jacques Cousteau. He wore a Brooks Brothers suit, a “shirt of sea island cotton,” and a silk tie, and was friends with King Hussein of Jordan and the King of Tonga. His other discoveries include: an Aepyornis egg, discovered in Madagascar; the Brazilian orchid Epistephium mardenii (yes, named after himself); a lobster parasite that became a new species of crustacean; the first report of underwater fluorescence. At age 70, he did a story on ultralights, small airplanes, and actually flew one.

Often, these men were neither conservative Republicans nor radical leftists, but represented the disciplined, open minds and questing hearts of classical liberalism at its best. When I met Bryan on the night in 1986, National Geographic itself was in a battle over its direction. My father and his colleague, the top editor Wilbur E. Garrett, had been pushing for years to do more relevant stories—not advocacy journalism, just stuff that engaged with grittier subjects like AIDS and life in Harlem. Opposed to them was Gil Grosvenor, who had been editor of National Geographic from 1970 to 1980 before becoming president of the organization. Tensions between Grosvenor, Garrett, and my father came to a head in 1990, when Grosvenor fired Garrett and my dad. The press depicted Grosvenor as the villain (accurately in my view), a stubborn retrograde man refusing to acknowledge that the world had changed. Circulation dropped.

After a rough transition period of a few weeks, my father settled into and enjoyed his retirement before succumbing to cancer in 1996. He never relinquished the John F. Kennedy liberalism of his youth—scientifically rigorous, Catholic, anti-racist (in an older sense of that word), pro-union, pro-environment, and pro-life. My father had written articles on Ireland, Jerusalem, Hong Kong, Australia, and South Africa. He ran the rapids in the Grand Canyon and produced a record on the space program for the magazine. In November 1986, National Geographic published the results of his five-year study to determine the location of Christopher Columbus’s landing place in the New World. Dad had discovered that the site was Samana Cay, a small isle about 65 miles from the traditional location, Watling Island.

Today, National Geographic, like so much of the rest of the culture, seems gripped in a mania focused on guilt over race and gender. As part of the magazine’s April 2018 “The Race Issue,” editor Susan Goldberg offered this headline: “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It.” Goldberg hired a scholar, John Edwin Mason of the University of Virginia, to dig through the archives and find white supremacy. Interviewed by Vox, Mason announced that “the magazine was born at the height of so-called ‘scientific’ racism and imperialism — including American imperialism. This culture of white supremacy shaped the outlook of the magazine’s editors, writers, and photographers, who were always white and almost always men.” Responding to a 2018 cover featuring a cowboy on horseback, Mason argues that “the image of the white cowboy reproduces and romanticizes the mythic iconography of settler colonialism and white supremacy.”

And then there was the ridiculous hagiographic Fauci, a documentary that gives the impression that the proper response to public authority is unquestioning obedience and unceasing praise.

Susan Goldberg has just announced she is leaving the editorship of National Geographic after nearly twenty years. I have little hope that the magazine or the organization will correct course. It has been captured by the current of political correctness, and there is no turning back. It provides another example of the death of what was once the best of liberalism. Before being corrupted by wokeness and overtaken by our Stasi media, liberalism was a questing, largely honest ideology that sought to correct injustice while also celebrating the foundational principles of free speech, hard work, and scientific rigor. Before the woke revolution, National Geographic lived these values.

Bryan exemplified such a spirit. He didn’t expose the lies surrounding Michael Mullen’s death out of hatred of America and her institutions, but to reveal how governmental lies had deceived a proud American family about the death of their son. In 1976, The New York Review of Books ran a review of Friendly Fire by Diane Johnson. The piece criticized Bryan, claiming that he was “patronizing” and “condescending” to the Mullens while letting off easy military men like Lt. Col. Norman Schwarzkopf, who had been in Vietnam and who was interviewed by Bryan. In a response printed in the letters section, Bryan punched back:

I love Peg and Gene Mullen, they have been as family to me these past five years, I think them heroic people. Ms. Johnson’s implication that I felt “patronizing” or “condescending” or “deprecated Peg’s courage” is so patently wrong that I am ashamed such a suggestion might even appear in print. […]

What I tried to show was that this lowa farm family’s anger, bitterness, paranoia, suspiciousness, and heartbreak were the understandable and inevitable result of the insensitive, arrogant, and bureaucratic treatment they had received—and not just from the military, the government, their community, and their priest but, to my horror, from myself as well. I was forced to face that ugly dwarf-soul in every writer who, when confronted by someone’s personal anguish, feels that flicker of detachment which tells him that he is also witnessing “good material.” . . .To admit that does not mean one does not feel sympathy and love and understanding at the same time; it merely means that the writer recognizes that this moment of anguish provides a means of expressing that anguish to others.

He closed with this:

I do not accept Ms. Johnson’s implication that because Lt. Col. Schwarzkopf was a professional military officer that he could not also be a fine man. . . . Why is it so inconceivable to Ms. Johnson that Gene Mullen and Norm Schwarzkopf could not both be fine men?

Liberalism could once see that both of these men could be fine men. It could question America’s war yet honor her warriors. Also, Bryan’s admission that his “dwarf-soul” saw in the Mullen’s grief “good material” is a grown-up confession that one would never find in the modern media. For all their swashbuckling derring-do, National Geographic writers, often awed by the world, could express genuine humility.

Like my father, they knew mysticism was a healthy part of the human psyche even as science is essential to progress and understanding. Science seems a lost civilization in National Geographic’s issue on “the gender revolution.” The section titled “Helping Families Talk about Gender” offers this: “Understand that gender identity and sexual orientation cannot be changed, but the way people identify their gender identity and sexual orientation may change over time as they discover more about themselves.” As Andrew T. Walker and Denny Burke wrote in Public Discourse,

the first half of this sentence asserts the immutability of gender identity, but the second half of the sentence claims that people’s self-awareness of such things can change over time. But is there not a contradiction here once we define our terms? Gender identity is not an objective category but a subjective one. It is how one perceives his or her own sense of maleness or femaleness….If that perception is fixed and immutable (as the first half of the sentence asserts), then it is incoherent to say that one’s self-perception can change over time (as the second half of the sentence asserts).

Another article offers a full-page picture of a shirtless 17-year-old girl who recently underwent a double mastectomy in order to “transition” to being a boy. Walker and Burke: “Why do transgender ideologues consider it harmful to attempt to change such a child’s mind but consider it progress to display her bare, mutilated chest for a cover story?”

When seeing such nonsense, I think back on C.D.B. Bryan’s little joke to me more than thirty years ago, but in a new context: National Geographic is a great place to be. Still, I don’t know if you’d want your daughter dating someone from there.