Prospects for Inflation

Richard Reinsch (00:04):

Today we’re talking with David Goldman about prospects for inflation in the American economy. We’re glad to welcome David Goldman back to Liberty Law Talk. He’s a senior writer for Law & Liberty. He’s the president of Macrostrategy, and he writes the Spengler column for Asia Times Online. He’s the author of a number of books, including You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World. David, glad to have you on the program today.

David Goldman (00:50):

Richard, it’s a great pleasure to be back. Thank you so much for inviting me.

Richard Reinsch (00:53):

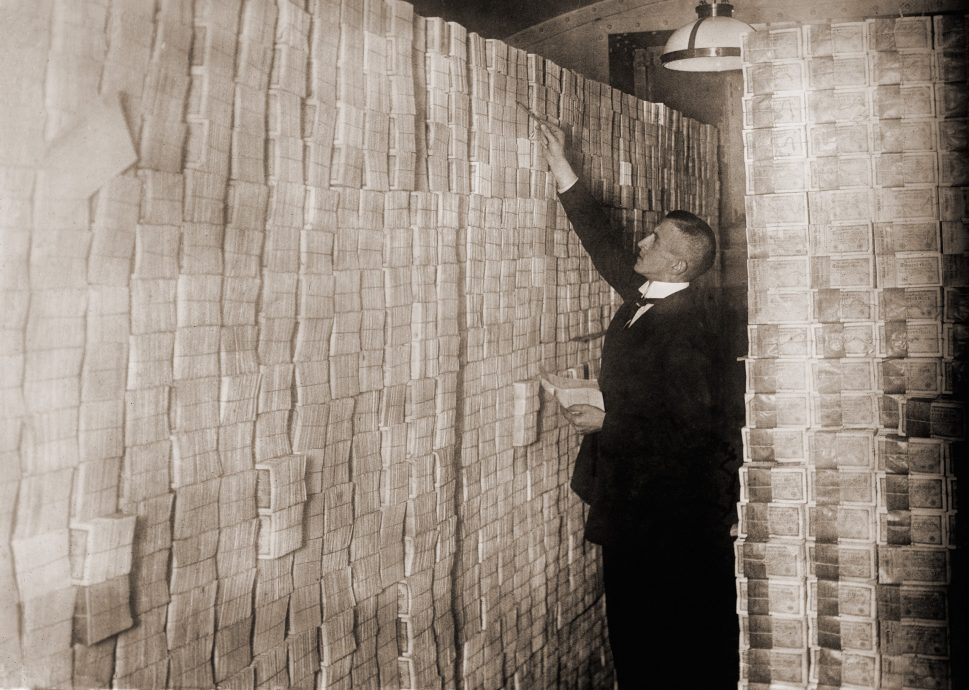

We’re glad to have you on this topic, in particular. The smart people tell us that inflation fears have subsided. There are a group of economists who strangely call themselves modern monetary theorists, who argue that we can take on an unceasing amount of debt and spend it however we want on various social programs, environmental programs, and none of this will have untoward results or result in things like inflation. We’ve spent, rounding up, $5 trillion in pandemic stimulus recently, almost 3 trillion, 2.9 trillion in expenses. And I’m told the Biden administration wants to spend another $3 trillion on infrastructure and climate change policies. What do you make of all of this? And what would it mean for the value of the dollar, this incredible spending?

David Goldman (01:46):

Well, I think in the short-term perversely, the dollar is likely to go up, but then I think it’s going to go way, way down as a result. And ultimately this largess will threaten the dollars global standing as a reserve currency and America’s capacity to finance itself on the scale we have in the future. The numbers you cited are truly astonishing, by historical standards. We’re presently looking at a deficit, including this $1.9 trillion of stimulus just passed, at roughly a fifth of our gross domestic product. We haven’t done that in the past, except during war time. The last time we had a deficit that big was in fact in 1945 and the Federal Reserve is financing virtually all of that because there simply isn’t anyone else in the world with the wherewithal or the desire to own that many treasury securities.

David Goldman (02:47):

Just to give an example, after the 2009 crisis, we ran a big deficit, not nearly this big, foreigners financed about half of the Obama debts. Foreigners so far have financed zero of the net treasury issuance over the past year, which is ominous. So there’s really nobody in there, but the Federal Reserve and US financial institutions doing that. Now, does this turn into realized inflation? A great part of the problem we have is the measurement of inflation. Every American family has two really big ticket items on their budget. One is the house and the other is the car. Now, the price of houses in the United States has gone up 10% in the past year, more than 10%. So we’re back to the level of housing price inflation, if that’s the right word, that we had at the peak of the housing bubble in the mid 2000’s. We haven’t seen that kind of housing price increase since 2005, except briefly when we hadn’t recovered from the crash. And the price of used cars and trucks is up 10% over the past year.

So when you say we can tame inflation, how do you do that? You can take money away from people so they can’t spend money, that would tame inflation. You could send the police round to take money out of everybody’s bank account, hypothetically, that would tame inflation, but is that a solution which would help us or be politically acceptable? I don’t think so. I think the Federal Reserve has a tiger by the tail. They don’t fear it, let it go.

So, from the standpoint of affordability of life for an American family, the situation’s quite dire. But if you look at the consumer price index published by the American Bureau of Labor Statistics, it’s only up 1.7% year on year and fed chairman Jerome Powell has said, “Well, we think inflation of 2% is kind of a desirable thing.” That’s a whole other question. We’re well below that. So I’m not worried about inflation. Now, the way the Federal Reserve measures such things is, for example, they don’t look at the price of a house. That’s a capital investment. They look at the cost of rent. Now rents are actually moving very modestly, but in a situation where the federal government has an eviction moratorium and vast numbers of Americans can’t pay their rent, that number is completely meaningless. So, I submit that the 1.7% year on year at consumer price index number, doesn’t really reflect what American families have to pay. That the explosion of housing prices, and explosion of used car prices is a much better indication.

So inflation’s already hurting people badly. And if we keep pumping stimulus in, but we don’t have the productive capacity to meet the spending power, one of three things could happen. One is prices go up. So the amount of money spread over a smaller amount of goods becomes less valuable, the value of money goes down. The second thing is that people stop buying things because prices are going up, so the economy either slows or goes into recession. And the third thing is we import a lot more from China. And all those are happening, at the same time.

Richard Reinsch (05:59):

So you’re saying we already have inflation in asset prices.

David Goldman (06:04):

That’s correct. And they’re assets which every family has to accumulate. There are very few families in the United States that can do without a house and a car.

Richard Reinsch (06:14):

And that would include, when we say asset prices, we also mean equities in that as well.

David Goldman (06:18):

Yeah. So equity prices have gone up, there’s a nearly one for one correspondence between the so-called real interest rates, so the rates on medium term inflation index treasury bonds, and the price, say, of tech stocks. So there’s absolutely no question if looking at the numbers that the Federal Reserve monetary stimulus, which has included zero interest rates for deposits and negative yields, real yields your terms are your securities, no question that this has put a lot of error into the stock market.

Richard Reinsch (06:52):

So inflation is here. Because I guess that doesn’t seem to be widely discussed or widely known in, say, popular accounts or press accounts of what we’re dealing with. But what we do seem to hear a lot about is this notion that we have very low inflation and to the extent, as Chairman Powell has said, Secretary Janet Yellen, that if we see inflation start to creep up they can tame it relatively quickly with conventional tools. And you’re arguing, that’s not true.

David Goldman (07:23):

Well, inflation could be a demand side or a supply fund phenomenon. One of the things that’s most distressing about the state of the US economy is chronic underinvestment in capital equipment and infrastructure in the means of producing things. In real terms, orders for capital equipment are back where they were in the 1990s. So US manufacturers have done very little investment in the past 10 to 15 years. Our production capacity, our supply chains are now constrained. So we have a large number of press accounts and studies coming out saying that as all this demand pours into the economy, manufacturers simply don’t have the supply chain capacity, the production capacity to meet the demand. And many reasons for that, part of it’s blamed on the Texas weather. Part of it is blamed on a global semiconductor shortage, but I think all of the blame is we haven’t been investing in manufacturing capacity and in infrastructure, and that’s had some really perverse effects.

So when you say we can tame inflation, how do you do that? You can take money away from people so they can’t spend money, that would tame inflation. You could send the police round to take money out of everybody’s bank account, hypothetically, that would tame inflation, but is that a solution which would help us or be politically acceptable? I don’t think so. I think the Federal Reserve has a tiger by the tail. They don’t fear it, let it go.

Richard Reinsch (09:08):

About the Fed policy, and you’ve mentioned the Federal Reserve buying the debt. So you’re saying of the 5 trillion, roughly 5 trillion we’ve spent in pandemic stimulus, most of that has been issued by treasury and purchased by the Federal Reserve and other US banks. And I want to try to lead into a question on the policy of interest on excess reserves by the fed and what role that’s playing in all of this. How do you see that?

David Goldman (09:34):

I think the excess reserves issue is relatively minor. The management of excess reserves affects the extent to which commercial banks are able to buy treasury securities and make loans. Banks have been a significant contributor, net purchases are in the range of about $400 billion in the past year, which is roughly a tenth or so, of the total amount of financing required, but I don’t believe that’s a decisive issue. I think the critical issue is interest rates, the deficit, and the fact that the giant sucking sound here is all the capital in the United States going into financing the deficit.

Richard Reinsch (10:18):

I guess the reason why I asked that question is some say that the policy of interest on excess reserves allows the fed to both monetize the debt and curtail inflation because the money is then parked. And these banks fed reserve accounts does not immediately go out into the economy or competes with other rates.

David Goldman (10:38):

Yes. I mean, technically that’s true. If you look at M2 money supply, it now stands at about $20 trillion. And if memory serves me, roughly a quarter of all the money ever created at American history has been created in the past two and a half, three years. That’s a staggering rate of monetary expansion. But as the textbook says, it’s not the amount of money that determines the price, it’s the amount of money, times the velocity of money, how fast it turns over. And it’s true that the excess reserves policy keeps money parked and reduces the velocity of money. But that is a relatively minor thing because as the commercial bank, if you have customers who are willing to take on debt and they’re credit worthy, you want to make commercial and industrial loans for them. Whatever the excess reserves policy, that’s going to affect your incentive to do so in a relatively minor way.

David Goldman (11:42):

The main thing happening right now in the banking system is that people are not taking on debt, commercial and industrial loan growth is shrinking. In fact, the volume of commercial industrial loans has shrunk over the past 12 months of pandemic. Instead the banks are buying treasury securities and that’s because the kind of customers who typically are the big borrowers at the banks, the small and medium sized enterprises, have been flat on their back and aren’t taking on debt, or aren’t able to take on debt because they’re not credit worthy. Large corporations tend not to borrow from banks, they tend to borrow rather on the bonds. There’s been an enormous amount of corporate borrowing, but the medium-sized smaller companies who tend to use bank loans, don’t have access to the bond market, happen off the market. So I think it’s really the… Velocity of money issue is really a matter of the demand for bank loans and not the management of reserves.

Another way things could happen is that inflation really takes off. And that creates so many distortions that eventually the Federal Reserve is forced to raise interest rates, call a halt to this, and then we have a real bind because if we have US debt equal to our gross domestic product, and it’s increasing at 20% of GDP a year, for every percentage point that our debt increases, we pay another $250 billion in interest. Let’s say we go up three or 4%. Suddenly our interest builds us up by another trillion dollars and exactly at the point where we are forced to reduce borrowing, we also have to increase spending to pay the interest. In other words, we look like Italy during its economic crisis of several years ago. We look like a third world country, look like Turkey and at that point, we’re in a world of pain.

Richard Reinsch (12:40):

Thinking about the Federal Reserve’s policy. We have this piece we published by Alex Pollack a few weeks ago, inflation comes for the profligate, and he says the Federal Reserve has purchased including unamortized mortgage premiums, a sum of 2.3 trillion. Which is, Alex says, 2.6 times its total assets in 2007, I guess, meaning the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. That’s got to be part of the earlier comments you made about entering into a new housing bubble.

David Goldman (13:13):

Absolutely. Well, when you push mortgage rates down to one and a half percent, then the number of people who can buy houses is enormous. People have long memories. Back in the 1970s, there was only one major asset class that showed positive real returns, and that was houses. Stocks lost money, bonds lost money, well gold made money. But for most people, the American middle class didn’t do all that badly in the seventies because if you bought a house, you had the positive real returns. Now that was in a situation where family formation was much higher, we were at the peak of the baby boom. People born in the late forties and early fifties were then just forming families and buying houses. So the inherent demand for houses was higher, but still, from the standpoint of the ordinary American family, if you have the ability… Housing prices are running at 10% a year, and you can take a mortgage at 20% down, then you’re making 50% a year on your down payment, in fact your invested capital. That’s a very good rate of return.

Richard Reinsch (14:27):

Yeah, as you would say, what can’t go on forever won’t go on forever. That seems to be true-

David Goldman (14:34):

The famous Herb Stein law.

Richard Reinsch (14:35):

Yeah. Just in thinking about all of this. So the Federal Reserve continuing to buy the securities, continuing to monetize the debt and grow its balance sheet. What’s the end game for that?

David Goldman (14:47):

Well, there are several possible end games, but all of them are ones that we don’t want to see. One is that, as real returns to US financial assets are effectively suppressed, the rest of the world effectively stops holding dollars. Now to give an idea of the size of that, I estimate the low interest loans, which we’re getting for the rest of the world, at around $25 trillion. That’s about eight to 9 trillion of foreign holdings of treasury securities and 16 trillion of dollar deposits in overseas banks, which are held as working capital for international trade or international capital flows. That’s what’s called seignorage or the premium that a country gets for effectively having reserve currency, it’s used for the difference between what the King got for minting coins, the difference in the value of the coins and the bullion they were minted off, but the term persists. And if the Federal Reserve keeps real returns negative forever, eventually people will stop using the dollar and then we will lose loans to the rest of the world, which now amount to more than a year’s gross domestic product, we can’t sustain that.

And modern monetary theorists say, well, look, the Federal Reserve can print money and the US government can borrow all it wants at effectively a negative real interest rate. The interest rate on five-year, carefree, inflation protected securities is -1.7 percentage or so. So, at a privilege, if I buy effective security for five years, for the privilege of letting the US government use my money, I’m losing 1.7% a year in real terms. Or I would expect to be, just based on expected inflation. And that’s a great deal for the US government, but it’s not a great deal for the creditors of the US government. So eventually we’d lose the dollars. And if you read publications close to the state council of the Chinese government, the Chinese Communist Party, I’ve read article after article saying the US, because it has a global reserve currency, can get away with it for a certain period of time but eventually that’s going to wipe out the dollar’s role as a reserve currency, and that’s the end of American power.

That’s one way things could happen. Another way things could happen is that inflation really takes off. And that creates so many distortions that eventually the Federal Reserve is forced to raise interest rates, call a halt to this, and then we have a real bind because if we have US debt equal to our gross domestic product, and it’s increasing at 20% of GDP a year, for every percentage point that our debt increases, we pay another $250 billion in interest. Let’s say we go up three or 4%. Suddenly our interest builds us up by another trillion dollars and exactly at the point where we are forced to reduce borrowing, we also have to increase spending to pay the interest. In other words, we look like Italy during its economic crisis of several years ago. We look like a third world country, look like Turkey and at that point, we’re in a world of pain.

David Goldman (18:33):

So those are the two principle outcomes. And I don’t think any of this will happen at a one-year horizon, but at a five-year horizon it’s very possible. And if you can imagine the United States will wipe something like a quarter of personal income over the past year is coming from government cheques of one kind or another, and you’re forced to cut that back. The hardship on Americans and the shock to American politics would be horrendous, very difficult for any of us to conceive.

Richard Reinsch (19:06):

So that inflation episode, the way you try to get control of it is dramatic cuts in spending and dramatic increases in taxes, with hardship all around.

David Goldman (19:16):

Yeah. Well, look at Italy. Look at Greece. Look at third world countries that have been through this. Or even so look at Britain during the Sterling crisis of the 1960s and 1970s. I was a graduate student in London in 1974 and 1975. And I remember the lights out in Piccadilly circus. This was a poor country in deep crisis.

Richard Reinsch (19:42):

Talk about that. How did that affect Great Britain, when that moment happened?

David Goldman (19:46):

Well, people were pretty miserable. Britain went from being a global power to being a second rate power, to being much less important. Margaret Thatcher fortunately came in and set things right, but the North of England has never really recovered. So the United States could end up being a second rate economic power, while China becomes a dominant power in the world as a result of this. I’m not against spending money from the federal government, Richard. If Biden had said, let’s spend 1.9 trillion on infrastructure, research development and STEM education, I wouldn’t be unhappy about that. But simply to put money into people’s pockets in the hopes that they spend more means, namely, that they buy more smartphones and computers from China, and China’s exports to the United States are soaring.

Richard Reinsch (20:38):

As I was doing research for this interview, I came across a number of articles where people would take on your argument that you’ve made and say, yeah, but people were saying this in 2009, people were saying this in 2008, that America would become like Greece or America would become like Italy and it didn’t materialize. And it didn’t materialize for a number of reasons, many of which we’ve discussed or touched on. And this global reserve currency thing is noted, this need to hold dollar denominated deposits, trade situation. And America is the best deal on the block sort of thing. We can do more. And what do you make of that? Here we are, 10 years later, we’ve dramatically increased the money supply, dramatically increased public spending. We seem to be in this late great society, 1960s mentality regarding government program thinking. And what of it? How do you respond to that?

David Goldman (21:34):

Well, I think from the standpoint of American families, the outcome wasn’t particularly desirable. We had, under the Obama administration, effectively eight lost years, where we never got back to the trajectory of growth that we have in the past, we had chronically low growth. The economy in 2016 was about 10% smaller than it would have been if we had had a normal economic recovery, if we’d caught up and compensated for the lost growth of the great financial crisis. So I think the dissatisfaction in large parts of the American population, which gave rise to Donald Trump’s populism, is a pretty good gauge of how unsatisfied most of us were with the outcome after the standpoint of investors in Facebook and Google and Microsoft, things were great. The other thing in terms of the dollar US international role is we really didn’t have any competition. The Europeans were in some ways in worse shape than we were, Europe went through a severe financial crisis in the early 2010’s, parts of it are still in very dodgy condition.

So although the international use of the Euro has grown at the expense of the dollar, the Euro simply isn’t likely to substitute for the dollar as a world reserve currency because Europe has its own weaknesses. The difference now is we’ve got shot. China has its own problems, but China is 15% of world exports and only 5% of world stock market capitalization. The Chinese are very cautious about opening their capital markets in such a way that would allow their currency, the RMB, to become a global reserve currency, at least for the present, but on the five or 10 year horizon the Chinese have ambitions to make the RMB a global reserve currency. And if China’s economy continues to grow faster than ours and the Chinese manage to realize their extremely ambitious national program for the fourth industrial revolution, and they manage to assert themselves as the leading technology power in artificial intelligence and the 5G telecommunications manufacturing and so forth.

Then at a five to 10 year horizon, we will have a challenge that can push us out of first place. And this is not a nice competition we’re involved in, this is Glengarry Glen Ross, first prize is a Cadillac, second prize is a set of steak knives. If you lose your ability to borrow in your own currency globally, that is reserve status, and you lose the dominant position in the world market for high tech. It’s not just Huawei that’s the dominant telecom producer, but if Chinese companies are the dominant AI providers in a number of fields, then the United States would go through a decline similar to what Britain went through in the 60’s and 70’s, it doesn’t mean we disappear as a country, but it means we have lower living standards. We have even more deeply fractured body of politics. We have less military power and generally we hate life.

Richard Reinsch (24:57):

Those are the stakes. Related question, is just thinking about China. What did China learn, do you think, from our financial systems near collapse in 2008 and the way we managed that crisis?

David Goldman (25:12):

Well, China was terrified by that, in 2008.

Richard Reinsch (25:15):

And I suppose the related question is how did they change their approach to us, also?

David Goldman (25:21):

Well, the most important thing that the 2008 crash did was to persuade the Chinese that they shouldn’t emulate the American model. We now say with 2020 hindsight that the Chinese would never change, they’d never reform, they’d never be like us, that letting them into the World Trade Organization was a terrible mistake, that believing in Chinese reform was a terrible idea. But in fact, before 2008, there was a substantial body of opinion in China who said look at this wonderful American model with its technological marvels and its incredible living standards. We should be a lot more alike. After 2008, the Chinese said, this thing was a scam. The Americans are running a bubble, they’re hollow inside. We’re going to do things our own way.

Now that’s a very long-term proposition because, from the Chinese standpoint, remember in 2007, something like 35% of China’s GDP went to exports. They were completely dependent on the American market and they very narrowly avoided a severe recession when we went into recession. Now the export dependency has fallen by roughly half. China’s exports to the world are 17% of GDP and much smaller amount is exported to US. And they’re determined to be less dependent on exports over time and build up the domestic market because they don’t see the United States as a viable prop for their growth. So to the extent that the 2008 crisis put us flat on our back, it persuaded the Chinese to challenge us, to become more aggressive and pursue a policy quite different from ours, not to reform and to challenge us eventually.

Richard Reinsch (27:21):

I think I know your answer to this, but I think a lot of our listeners would gain from hearing it. Modern monetary theorists would point to, and this surprises me, but countries like Japan that have taken on a lot of debt, I mean much more than we have. I think Japan has 240% of GDP, more than twice the American ratio, but why couldn’t we be just like Japan and just continue to take on debt and support a lot of social spending that a lot of Americans apparently now want.

David Goldman (27:50):

If you’re a net lender to the rest of the world, as Japan is, Japan has a net foreign asset position of about plus $4 trillion, if I’m correct. Several trillion dollars. The United States by contrast has a net foreign asset position of negative $13 trillion. If you can fund your deficit with domestic savings, then effectively, what you’ve got is the Japanese owing money to each other and they can keep doing that as long as they feel like. It certainly hasn’t been optimal for Japan, Japan has had very low growth, but part of the very low growth is a rapidly aging population and a declining workforce. Part of the reason for so much saving in Japan is because people approaching retirement save a great deal more.

So, for a whole bunch of reasons, Japan doesn’t look like us at all. My point, Richard, is that if you’re running a current account deficit of 60, $80 billion a month, and you have a net foreign asset position at negative 13 trillion, then your ability to finance a deficit of 20% of GDP becomes very dodgy and particularly, and it’s not just the net foreign asset position. If you look at, as I’ve said, the total holdings of dollars globally, and how much credit the global reserve position of the dollar allocates the US, we’re talking 25 to $30 trillion, by my estimate. And if that starts to erode, if foreigners say, “Well, we just don’t need the dollar anymore. Why should we hold these balances? Why should we hold those treasury securities at a negative yield?” And at that point, we’re in a world of pain.

Richard Reinsch (29:38):

When you say America has a net international investment position of negative 13 trillion, what does that mean exactly?

David Goldman (29:47):

It means we’ve imported net $13 trillion of capital more than we’ve exported. We either owe foreigners or have foreign investments in our stock market of $13 trillion. Our monetary system, our economy has been dependent on capital flows coming in, and that roughly corresponds to our trade deficit over the past 40 years. If we keep importing more than we export, we’ve got to give people our paper, our IOU’s for that difference. We sell them assets, we sell them bonds, stocks or whatever. That’s how you get a negative net foreign asset position.

Richard Reinsch (30:27):

And right now we’re balancing that with being the world reserve currency or buffering that somewhat?

David Goldman (30:33):

That’s correct. I mean, it’s also true that this capitalization to the US stock market has helped, that’s a fact that some of our tech companies have been so successful has attracted a lot of foreign capital. So what worries me is not simply the monetary situation, it’s that if the Chinese become the dominant players in artificial intelligence and the next generation of great tech companies with mega market capitalization, the next Googles and Microsofts and Apples and so forth are Chinese companies instead of American companies, then we could be in double trouble.

Richard Reinsch (31:11):

And you and I talked a lot about that in our previous podcast, when we discussed your book, You Will Be Assimilated, on China’s policies there. And I assume you still hold most of those views that China’s tech prowess is going to outpace us soon.

David Goldman (31:26):

That’s a view which has been widely expressed by people who know a great deal about it. There was a report about three weeks ago by an entity called the National Security Council on Artificial Intelligence, a report shared by Eric Schmidt, former chairman of Google and Robert Work, who was deputy secretary of defense in the Obama administration. Now Work is extremely bright. And that report said that there is a very significant danger that China will dominate the trademark industry, trademark technology, which is artificial intelligence with of course, applications to many industries. And they propose some very dramatic measures to avoid that.

Now China is spending $600 billion a year in US dollars on technology subsidies, support, R and D and so forth. The United States is spending a fraction of that and that $600 billion, by the way, in China buys a great deal more skilled manpower than it does in the United States because qualified engineer salary is about a third of that in the United States. So the Chinese are outspending us massively on the cutting edge technologies which very well may define the economy of the 21st century. And we’re in danger of falling behind, the Biden administration has said some reasonable things about the need to catch up, but they haven’t done anything or proposed anything serious so far.

Richard Reinsch (33:01):

You and I have been talking and I know you’ve had a lifetime in capital markets and finance and economics. And we’ve been talking a lot about those concepts and consequences of abusing certain notions in finance and capital markets and fiscal policy. But to what extent also, and I suppose it’s not either, or, it’s related, is America’s position, and a relatively declining position it seems, do also it’s not that we don’t understand these things. It’s we lack the virtue, the seriousness, the desire to discipline our appetites and have a medium and long-term perspective on what’s best for this country. And that includes also our leadership class. How do you see that?

David Goldman (33:43):

A Chinese acquaintance told me you’re having your cultural revolution now with your struggle sessions and your policy of sending people to go out and work with peasants. What’s happening at our universities where engineering departments are run by diversity deans is quite concerning, but apropos of your point, it’s not simply the work lacks, I think that the national sense of virtue is, to put it mildly, challenged. By way of contrast, in China, 10 million high school kids take the university entrance exam, the gaokao, every year and admission to universities, which is a sure determination of a future career, is entirely determined by your exam score. Your grades, your club membership and so forth, your sports don’t count at all. So only that single grade, people have studied for years, the average Chinese family spends a year’s income on tutoring. The average. 50% of the kids to take the gaokao in China will fail. Won’t get a university position. They’ll go to a trade school to get some technical education, but they won’t get to university.

David Goldman (35:01):

The Chinese set the bar so that half of the contenders will fail and the Chinese people are willing to accept 50, 50 odds. And the fact that the Chinese have such a ruthless, and in many ways heartless meritocracy, which demands so much effort and so much competitiveness from their kids, gives them an advantage. That’s the kind of thing you used to hear in top law schools, where the Dean would tell the incoming class, look to your left, look to your right. One of you isn’t going to be there in three years. That kind of competitiveness and willingness to work is something we’ve lost. Chinese schools, they’ve got to make kids do calisthenics because otherwise they study all the time and waste away.

Richard Reinsch (35:50):

I think that’s a fitting way for us to end as we think about what America has to do to get its house in order. Part of that is just the recovery of discipline and the willingness and the desire to succeed. Thank you so much, David Goldman, we’ve been talking about the prospects for inflation.

David Goldman (36:06):

Thank you Richard, it’s been a pleasure talking.