Were the founders influenced by Christian ideas? That’s the question Hall wants to pursue.

English Dreams in American Soil

Two decades into the twenty-first century, the Enlightenment is increasingly depicted in a negative light. Some in the postliberal New Right largely view the Enlightenment as the beginning of the decline of the West. Instead of celebrating capitalism, liberalism, and empirical science as forces that propelled the West and the wider world, they view these Enlightenment phenomena as the root of selfish individualism, rapacious monetary policies, and destructive and enslaving technology. For some on the political left, the Enlightenment was a horrific period of colonialism and the emergence of Western nations as rulers of the globe.

The situation is, of course, much more complex. The Enlightenment means many things, but it was especially crucial to the emergence of English liberty. In his recent work, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: Britain and the American Dream, English historian Peter Moore presents a fascinating and complex analysis of the English roots of American liberty. Moore begins his work with the clever statement: “Britain first dreamed the Enlightenment dream, but it was America that made it happen.” Moore notes that Britain was regarded as the great revolutionary nation for most of the eighteenth century. The revolutionary ethos of Britain began with the 1688 Glorious Revolution, which gave birth to the 1689 Bill of Rights. Britain was known throughout the eighteenth century as a land of progress, freedom, and science, populated as Moore notes, by figures such as Joseph Addison and Sir Isaac Newton.

During the 1760s, however, American colonists developed the notion of a plot against their liberty. The notion of a conspiracy against liberty, Moore argues, is rooted in the coronation of King George III in 1760, in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, and also in subsequent taxes levied on the colonies in 1765 and 1767. Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness is about how Britain helped give birth to the American Revolution. Moore argues that the Enlightenment provided the West with a new vision of life, which included freedom and ambition in a (largely but not entirely) secular context. This view was, of course, rooted in liberty and tied to the notion of the possibility of happiness in this life. For Moore, all of these ideas, which seem so distinctly American, are in fact deeply rooted in the English tradition. Moore sees England as the ultimate seedbed of liberty as well as the locus of the creation of a new way of life focused on enjoyment in the here and now of the secular world.

Moore’s Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness is structured around the lives of several major British and American figures, including better-known luminaries such as Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Johnson as well as lesser-known figures like Catherine Macaulay and John Wilkes.

Moore’s Benjamin Franklin is a complex figure who reflects the Enlightenment life of ambition. His life was geared around social advancement and success as a publisher and later an inventor. He was a working man, whose body was shaped by the labor attendant to printing, but he dressed well and was widely known as an intellectual. He was born in Boston to Josiah Franklin, a tallow chandler. After working for his father, Ben Franklin made his way to Philadelphia in a near penniless state but was, in a very Enlightenment fashion, able to climb his way up the ladder of progress to near the heights of Pennsylvania society. Franklin first established himself in newspaper publishing–another quintessentially Enlightenment trade. Newspapers like Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette opened up a world to the general public that had previously been very restricted. As Moore notes, people before that time had often lived relatively provincial lives rooted in their local community. Now, newspapermen like Ben Franklin could narrate tales, for instance, by relating the latest exploits of the Kellymount Gang in County Kilkenny, Ireland to Irish immigrants living in Philadelphia. Franklin also utilized his publications to wage war against his literary and political rivals.

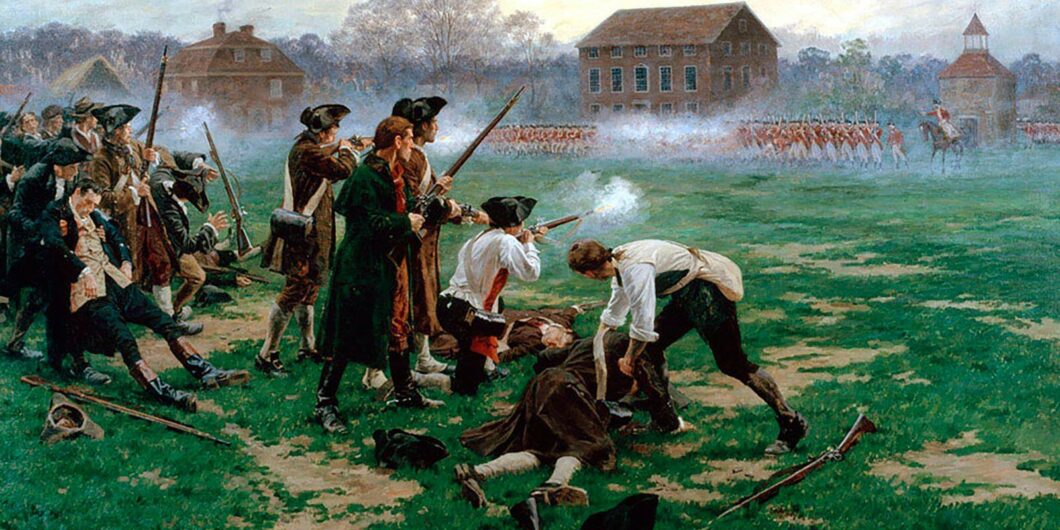

Ultimately, America became the land in which English liberty took root and developed into a bloody revolution.

One of the most crucial figures in the Enlightenment Anglophone world who took advantage of the newspaper’s power was the radical John Wilkes. A notorious libertine and radical, Wilkes founded the newspaper, The North Briton. Because of his writings, Wilkes drew the ire of the 3rd Earl of Bute, John Stuart, as well as King George III. Wilkes was eventually arrested for his writings and became a cause celebre for radical liberty. Wilkes went into exile and later returned to become Alderman of London and later Lord Mayor of London. Wilkes represents the wild and radical side of Moore’s depiction of the Enlightenment notion of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He demonstrates the tremendous power of the emergent press which can turn ordinary men into celebrities, strongly influencing the opinion of the public. Moreover, Wilkes represents the newfound Enlightenment ability of humans to challenge and even defeat the dominant monarch and aristocratic order.

If the American Benjamin Franklin and the English John Wilkes were the faces of the emergent, liberal Enlightenment man, the English Samuel Johnson was the quintessential Enlightenment conservative. Johnson, the son of a Staffordshire bookseller, was a volatile bibliophile, who, as Moore puckishly remarks, would fit Victor Hugo’s observation, “He never went out without a book under his arm, and he often came back with two.” Johnson, the author of the famous Dictionary of the English Language, was the star of the social clubs of London (another Enlightenment phenomenon). Although an Anglican Tory, Johnson was vehemently opposed to slavery (he thus was more an Enlightenment conservative than a harsh reactionary). Johnson did, however, detest the Whigs whom he thought too optimistic and too ready to dismiss traditional British culture and values. Johnson was also strongly opposed to Enlightenment deism. However, Moore makes special note of Johnson’s 1773 novella, The History of Rasselas: Prince of Abissinia, as strongly reflecting the Enlightenment pursuit of happiness, albeit with a strong element of traditional Christianity.

Set in the African kingdom of Abyssinia, The History of Rasselas tells the story of a prince who travels in search of happiness. Rasselas was born in “Happy Valley” where every human desire was present to him. However, secular comforts were not enough for Rasselas. Rasselas, along with his sister and the poet Imlac, travel the world in search of happiness, but it always slips through their grasp. Johnson’s overall point is that happiness is fleeting; the more one attempts to find it, the more elusive it becomes. Moore notes that Johnson’s Rasselas influenced Thomas Jefferson’s understanding of the pursuit of happiness as a quest that may not have an ultimate conclusion. This reflection is very curious and perhaps reveals a key lacuna in secular Enlightenment thinking. Having the freedom of mobility (both geographic and economic) facilitated tremendous financial success for many in the Enlightenment. Moreover, greater freedom of the press and inquiry arguably allowed for some important developments in human thinking. However, this freedom in itself did not lead to human happiness.

Ultimately, America became the land in which English liberty took root and developed into a bloody revolution. This revolution, though not as brutal as the later French Revolution, was nonetheless a major event in human history that put Enlightenment ideas into practice and created a new republic (as opposed to the English constitutional monarchy). However, since the advent of the American Revolution, the question of what exactly American liberty is has been debated. Some, such as more radical libertarians and libertines, have argued for an approach derived from the life and work of John Wilkes: liberty means radical freedom to do what one wants with little or no restriction. Others, such as Christian conservatives and, now, post-liberals, have argued for a view similar to that of Samuel Johnson: some moderate Enlightenment ideas should shape human life, but Christianity and traditional hierarchical social formation should provide a check on Enlightenment radicalism. Finally, others have argued for the moderate approach of Benjamin Franklin, using Enlightenment rationalism and moderation to guide one’s life. Throughout most of American history, these views have coexisted in tension with only occasional flare-ups (one of the most pronounced being the American Civil War). However, in the twenty-first century, it increasingly seems that these views can no longer stay in a relatively stable tension, and we are now, again, entering into a period of revolution.